This blog will expand on themes and topics first mentioned in my book, "The Automobile and American Life." I hope to comment on recent developments in the automobile industry, reviews of my readings on the history of the automobile, drafts of my new work, contributions from friends, descriptions of the museums and car shows I attend and anything else relevant. Copyright 2009-2020, by the author.

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

Cartoons and Caricatures of Driving in America, 1902-1909.

Friday, March 26, 2021

A Sunday Drive on the Hakone Turnpike

Where

Hakone Turnpike, Kanagawa, Japan

Length

14 kilometres, one way

Type

A classic Japanese ‘touge’ mountain pass, with smooth and sweeping bends surrounded by lush vegetation, topped off with unspoilt views of Mount Fuji.

As she prepared to return and set up home on the other side of the world in Los Angeles, Japanese teenager Kyoko Yamashita asked for just two things from her father: braces and a driver’s licence. And so began an early love affair with cars and car culture that would influence the marketing executive and self-confessed petrolhead right into adulthood.

Having grown up between LA and Tokyo, Yamashita travels regularly back to the Japanese capital, and it is from here that one of her dream drives starts. “I like to meet up with a friend or two for an early morning coffee in Tokyo before driving for around 90 minutes to the Hakone Turnpike. This is the starting point for one of my most satisfying driving getaways, and because I don’t get to drive it that frequently, I like to plan a whole weekend around it.”

The Hakone Turnpike is one of Japan’s most celebrated ‘touge’, the mountain roads synonymous with tuning and drift culture today. In this instance it is also a popular escape for many residents of the greater Tokyo area who want to get out of the city and back to nature. The area’s famous hot springs bring hard-working urbanites out in the droves for relaxing weekend breaks beneath the magnificent snow-capped peak of Mount Fuji.

Japan’s mini Nürburgring

“The road itself is quite short – about 14 kilometres,” Yamashita says, “but it’s a privately-owned toll road so it doesn’t get too busy. Obviously on the weekends you have your fellow motoring enthusiasts, both bikes and cars, but even then it’s not too bad. And the best part is that if you don’t exit the toll road on the other side, you can keep going up and down for as long as you like. Even though it’s a two-way road, lots of people refer to it as Japan’s mini Nürburgring.”

Around 100 km south west of Tokyo, the fastidiously maintained Hakone Turnpike climbs to over 1,000 m on an elevated road punctuated at regular intervals by rest areas and an observation deck at the summit complete with a cafeteria selling snacks and coffees for the onward journey. Surrounded by lush vegetation and with stunning views towards Mount Fuji, it’s a destination in itself but also a go-to route for local motoring media and manufacturers looking to put the latest hardware through its paces.

The Hakone Turnpike is not a typical alpine pass

“It’s not a super-twisty or high-speed road,” Yamashita says, “but it is very smooth and full of long, sweeping curves. It’s perhaps not as demanding as your typical alpine pass; I’d say it’s a little more relaxing while still being challenging enough. There are several blind corners and parts of the pass are high bridge sections, so you get a real sense of height as you climb the mountain.”

Entry through the toll costs 1460 Yen (around 11 Euros) and except in extremes of winter weather it is open year-round. Yamashita suggests trying to make the trip on either side of the summer months, however. “The best season to go is Spring when the cherry blossoms start blooming, one of those truly iconic images of Japan. But Autumn offers an amazing array of colours too – you’re surrounded by beautiful foliage everywhere.”

Yamashita’s Porsche history started with a 987 Cayman S

With Yamashita’s own cars back home in California, her perfect accompaniment for this drive takes her back to when the Porsche bug first bit. “In LA I have a 997 Turbo and an ’88 911 Carrera 3.2, both with a manual gearbox. They are special cars to me and I love them for different reasons. But my Porsche ownership history started with a 987 Cayman S. It was my first mid-engine car and the first car I took to the track. Many, many times in fact. I lived in San Francisco at the time and would go to Sonoma Raceway, Laguna Seca and Thunderhill. I had that car for nearly four years and it was really hard letting her go! I loved that mid-engine driving feeling, so for a road like the Hakone Turnpike, my preferred car would be a Cayman. Or maybe the 718 Spyder.”

A one-way trip over the Turnpike could take less than half an hour, but if you are determined not to double back, at the far end of the toll road you can pick up various alternative routes such as the Ashinoko and Hakone Skyline or the zig-zagging 401. “I usually jump on the road south for 40 or 50 km into the Izu peninsula,” Yamashita says, “where there is an area known for its early cherry blossom along the riverside. If I have the time I will drive down there and stay for the rest of the weekend.”

Relaxation is as essential an element of driving for Yamashita as the buzz it also clearly offers her. When asked if she has a go-to soundtrack for her road trips, her answer is enlightening. “I love music, but driving to me is a form of therapy. I used to be one of those drivers who had to have music on, but today I enjoy focusing on the road ahead and taking in the scenery. When I come back to Japan and get a chance to leave the busy streets of Tokyo behind, driving is very Zen for me. The sound of the engine gets the adrenaline going and I like the balance and the flow of just being in that moment.”

From Automotive News Europe, March 26, 2021

Mercedes-Benz is about to unveil a new flagship model it expects to boast market-leading battery range, following through on its pledge to compete in the luxury electric-vehicle segment with top technology.

The April 15 debut of the EQS -- the first Mercedes built on dedicated electric-car underpinnings -- will mark a milestone for the German brand that has been criticized for taking too long to embrace EVs.

Next year, Mercedes will be making eight fully electric cars on three continents, Chief Operating Officer Markus Schaefer said in a phone interview.

“We boosted flexibility of all factories worldwide so that we can produce hybrids, fully electric cars and combustion vehicles everywhere, depending on customer demand and individual market developments,” Schaefer said. “It took a while for us to prepare all this, but now it’s time to deliver.”

The more than 700 km (435 miles) of range Mercedes expects the EQS to achieve in lab testing is another indication Germany’s automakers will have something to say about Tesla's early domination of the EV space.

Volkswagen Group last week announced plans to become the new global sales leader no later than 2025, while BMW forecast battery-car sales will account for roughly half of deliveries by the end of the decade.

Mercedes is in the midst of a fundamental overhaul that will include a painful restructuring of combustion-engine sites that the manufacturer depended on for a century. The revamp has culminated in parent Daimler AG’s plan to spin off its truck operation this year, the most significant strategic move since the company sold off Chrysler.

Thursday, March 25, 2021

Nice Week, March 25-29, 1901: The Mercedes Brand Name was Born

Nice Week, 25 to 29 March 1901. Nice–La Turbie hill climb on 29 March 1901. Several two-seater racing cars in La Turbie. The second car from the left is the Mercedes 35 hp of Albert “Georges” Lemaître (2nd place), to the right is the Mercedes 35 hp driven by the winner, Wilhelm Werner (starting number 5). (Photo signature in the Mercedes-Benz Classic archives: R10386)

Nice Week, 25 to 29 March 1901. Photo of Baron de Rothschild’s Mercedes 35 hp, driven by Wilhelm Werner, on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. Emil Jellinek (with sideburns) is standing on the right behind the vehicle inside the barriers. (Photo signature in the Mercedes-Benz Classic archives: 1972M283)

Nice Week, 25 to 29 March 1901. Nice–La Turbie hill climb on 29 March 1901. Wilhelm Werner, who subsequently won the race, at the wheel of the Mercedes 35 hp owned by Baron Henri de Rothschild. Photo taken in La Turbie. (Photo signature in the Mercedes-Benz Classic archives: 71255)

No less than two milestones in the history of Mercedes-Benz were achieved by the important “Nice Week” racing event from 25 to 29 March 1901: 120 years ago, the era of the modern car began with the victory in Nice of the Mercedes 35 hp made by Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft and, at the same time, the Mercedes brand name was born. Emil Jellinek, at that time the most important dealer for Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG), named the high-performance car he commissioned after his favourite daughter Mercédès, who was born in 1889. In the years leading up to this, the motorsport enthusiast and businessman had already competed in a number of races under the pseudonym “Monsieur Mercédès”.

On 23 June 1902, DMG had applied to register the brand name Mercedes as a trademark, and on 26 September 1902 that brand name was registered and legally protected. In 1909, DMG also had the three-pointed Mercedes star registered with the Imperial Patent Office. The merger of DMG with Benz & Cie. in 1926 to form what was then Daimler-Benz AG resulted in the new Mercedes-Benz brand. Its tremendous global appeal since then was also reflected in the international brand report “Interbrand 2020”: Mercedes-Benz is the only German brand amongst the top ten “Best Global Brands” and the most valuable luxury automotive brand in the world.

The brand family of today’s Mercedes-Benz AG, as a globally recognised manufacturer of luxury vehicles, includes the car brands Mercedes-Benz, Mercedes-AMG, Mercedes-Maybach, Mercedes-EQ, G-Class and smart. This is supplemented by Mercedes me as the brand for digital services provided by Mercedes-Benz.

Crucial successes of the Mercedes 35 hp at Nice Week 120 years ago

Nice Week included a whole series of races and was a major motorsport event.

- Nice–Salon–Nice endurance race over 392 kilometres on 25 March 1901: Wilhelm Werner won the event at an average speed of 58.1 km/h. This went down in history as the first ever racing victory by a Mercedes car.

- Nice–La Turbie hill climb on 29 March 1901. Wilhelm Werner won in the two-seater racing car class in the Mercedes 35 hp owned by Henri de Rothschild (“Dr Pascal”) in a new record time at an average speed of 51.4 km/h ahead of Albert “Georges” Lemaître, also in a Mercedes 35 hp. The category of six-seater cars was won by driver Thorn at an average speed of 42.7 km/h, also in a Mercedes 35 hp.

- A further milestone success was in the record-breaking achievement by Claude Lorraine-Barrow in a Mercedes 35 hp, who set a new world record for one mile from a standing start, averaging 79.7 km/h on 28 March 1901 in a series of runs, which was also part of the five-day Nice Week event.

Luxurious automotive lifestyle

At the turn of the 20th century, Nice on the Côte d’Azur was an international centre of motoring culture. Especially in the winter months, the sophisticated upper class from all over Europe and also from overseas met here. Motorsport was one of the highlights of the luxury motoring lifestyle. The Nice–La Turbie hill climb had been staged since 1897. It is considered to be the first hill-climb race in the world to be officially held as a competition.

From 1899, the hill climb was the highlight of Nice Week. It was organised by the Automobile Club de Nice and the magazine “La France Automobile”. Emil Jellinek, whose family spent the winter periods in Nice, entered a Daimler 12 hp racing car with a “Phoenix” engine in 1899. The car, driven by racing driver Wilhelm Bauer, won the Nice–Colomars–Tourettes–Magagnosc–Nice race over a distance of 85 kilometres at an average speed of 34.7 km/h. In the prestigious Nice–La Turbie hill climb, Arthur de Rothschild took second place in the category of four-seater cars at the wheel of a Daimler 12 hp “Phoenix” at an average speed of 41.1 km/h.

Jellinek insisted on even more powerful cars from DMG for Nice Week in the 1900 season. In this way, the ambitious businessman became an innovation driver of automotive technology, which was still in an early stage of development. DMG responded by producing the 23 hp “Phoenix” car. However, Emil Jellinek’s involvement with two of these cars during Nice Week from 26 to 30 March 1900 came to a tragic end. The car driven by Hermann Braun overturned during the Nice–Draguignan–Nice endurance race – fortunately without any major consequences. During the Nice–La Turbie hill climb, however, experienced works driver Wilhelm Bauer had an accident in the Mercédès II just after the start and died a short time later as a result of the accident. Private entrant E. T. Stead won the tourist class in the Nice–Draguignan–Nice endurance race and the Nice–La Turbie over 296 kilometres in his own 23 hp “Phoenix” at an average speed of 48.4 km/h.

For DMG, it was an open question after these accidents as to whether the company should still participate in motorsport at all. Once again, it was Emil Jellinek who saved the day: instead of giving up, he urged the development of an innovative, safe and even more efficient car. Wilhelm Maybach, the company’s chief designer at the time, accepted the challenge and it was this that resulted in the Mercedes 35 hp, that is rightly regarded as being the first real modern motorcar. The first of these was completed at the Cannstatt plant on 22 November 1900, after which DMG test-drove it and improved it still further. On 22 December 1900, the company sent the car to Emil Jellinek in Nice. No less than seven of these super sports cars of their time, which were intended both for racing and for use as sporty private cars, were entered for the race week event.

The first modern car

The characteristic features of the Mercedes 35 hp were the long wheelbase, the light, powerful engine fitted low in the frame and the honeycomb radiator integrated organically into the front end, which was to become a hallmark of the brand. This car, which was highly innovative 120 years ago, marked the final departure from the horseless carriage style that was prevalent throughout the industry at the time. The innovations extended to the frame construction and the clutch technology. The sum total of the innovations – which were perfectly coordinated as a holistic system – made this vehicle the first modern motorcar.

Wilhelm Maybach’s great achievement demonstrated once again why he was given the honorary title of “roi des constructeurs” (king of the designers) in France, a country that had fully embraced motoring. The Mercedes 35 hp thoroughly impressed the experts during Nice Week 120 years ago. Paul Meyan, Secretary General of the Automobile Club of France, commented in a review of the five-day motorsport event: “We have entered the Mercedes era” (“Nous sommes entrés dans l’ère Mercédès”).

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

David Coulthard and Mercedes-Benz

- On 27 March 2021 the Scottish racing driver will celebrate his 50th birthday

- In 1996 he joined the Formula One team and drove for McLaren-Mercedes for nine years

- The first victory of the new Silver Arrows era in 1997 was to his credit

- His head of motorsport Norbert Haug: “David is and always will be a highly valued friend”

It is a rare feat for a Formula One driver to race for the same team for nine years. David Coulthard is one of those exceptions. “Between 1996 and 2004 he raced for McLaren-Mercedes 150 times and won 12 Grand Prix races in Formula One. From 2010 to 2012 he drove an AMG Mercedes C-Class in the DTM,” says Christian Boucke, head of Mercedes-Benz Classic. “Coulthard retained a close link to the company after his racing career – he was active as a Brand Ambassador for many years. On 27 March 2021 he will turn 50. Congratulations, David!”

The winner at Interlagos: David Coulthard won in a McLaren-Mercedes MP4-16 at the Brazilian Grand Prix in 2001

The first victory of the new Silver Arrows: For Mercedes-Benz, David Coulthard’s triumph on 9 March 1997 at the Australian Grand Prix was outstanding. It was not only the first victory for the McLaren-Mercedes team, but with the new black and silver design of the MP4/12 racing car it marked the birth of the modern, new Silver Arrows, which are still so successful to this day. The 1997 season opener in Melbourne was the beginning of a third era of Mercedes-Benz Formula One racing cars after 1934 to 1939 and 1954/1955. The silver McLaren-Mercedes had Formula One World Champions in the form of Mika Häkkinen in 1998 (McLaren-Mercedes MP4/13) and 1999 (McLaren-Mercedes MP4/14) along with Lewis Hamilton in 2008 (McLaren-Mercedes MP4-23). With the Mercedes factory team Hamilton, and one time Nico Rosberg, impressively continued this series of World Championships from 2014 to 2020.

A long career: In his third year in Formula One David Coulthard moved to the McLaren-Mercedes team in 1996. For nine years he drove alongside Mika Häkkinen and Kimi Räikkönen for the British-German team. His most impressive successes included the victories at the Monaco Grand Prix in 2000 and 2002 and at his British home Grand Prix at Silverstone in 1999 and 2000. In 2001 Coulthard came second in the World Championship. After 246 starts in Formula One and 13 victories, Coulthard ended his career in Grand Prix sport in 2008. He drove 31 races for the Mücke Motorsport team between 2010 and 2012 in the DTM with an AMG-Mercedes C-Class and in his last year as a racing driver came fifth at the Norisring.

The head of motorsport on his driver: Norbert Haug, Mercedes-Benz head of motorsport from 1993 to 2013, worked closely together with Coulthard for nine years in Formula One and three years in DTM. He calls the Scot a “highly valued friend, who has been a member of the Mercedes-Benz family for a quarter of a century, which is more than half his life”. The driver duo of Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard was characterised by the experienced head of motorsport as follows: “A real stroke of luck. Back then it was impossible to imagine a better combination of drivers – who respect and improve one another and, at the same time, have a great image and popularity.”

All-rounder: David Coulthard has handled the transition from elite athlete to entrepreneur, operating in many different fields very well. As a Brand Ambassador for Mercedes-Benz he was involved in marketing campaigns of new AMG models and in various events after 2011. “DC”, as he’s known in the paddock, runs his own film production company, accompanies Formula One as a TV commentator and is involved in hotels and restaurants. Coulthard enthusiastically drives historic racing cars on circuits or his own Mercedes-Benz 280 SL (W 113) on the streets of his home of Monte Carlo. He bought the “Pagoda” from the year of his birth, 1971, as his first very own car in 1995.

The early years: David Coulthard was born 50 years ago in Twynholm, Scotland, into a family obsessed with motorsport. His grandfather drove in rallies, his father Duncan Coulthard won a Scottish kart championship. On his eleventh birthday his father gave him his own kart and at 12 he became Scottish junior champion – the first of many titles. In 1989 he won the championship title of the British Formula Ford 1600 at the first attempt. David Coulthard was successful in Formula Three and Formula 3000 races. And he gathered Formula One experience as a test driver for Williams. When Ayrton Senna tragically died on 1 May 1994, Coulthard became a regular driver on the team of Frank Williams and in 1995 won the Portuguese Grand Prix in Estoril. In 1996 he switched to McLaren-Mercedes.

Friday, March 19, 2021

How the Electric Motor in Porsche Taycan Turbo S Works!

Please sit back. If you fully depress the accelerator pedal of a Porsche Taycan Turbo S, you will experience 12,000 reasons to choose a stable seating position. The driver and passengers are pressed into the upholstery in a manner that almost takes their breath away when the top model of the electric sportscar unleashes its collective torque of 12,000 Nm on all four wheels at once (Taycan Turbo S: CO2 emissions combined 0 g/km, Electricity consumption combined 28.5 kwh/100 km). The concentrated power is discharged in full without any delay and the thrust from the two electric motors on the front and rear axles remains virtually unchanged up to top speed.

This dose of adrenaline is the active ingredient in Porsche’s unique drive technology. It’s no coincidence that the renowned Center of Automotive Management (CAM) declared the Taycan the world’s most innovative model of 2020. At Porsche, innovation has always meant pushing technology to the extreme. In this case, that means exploiting the potential of the electric drive in a way that no one has ever done before.

Steered wheelhub motors from Ferdinand Porsche

Porsche did not come up with this concept just yesterday – or even the day before. In fact, it was more than 120 years ago. At that time, a young Ferdinand Porsche achieved a world first when he developed electric vehicles with steered wheelhub motors. The possibilities offered by electromobility spurred on his sporting ambition, and his racing car became the world’s first all-wheel-drive passenger vehicle.

The simple DC motors of yesteryear have long since been replaced by more sophisticated machines. However, the basic physical principle has remained the same: magnetism. A magnet always consists of a north and a south pole. Unequal poles attract; equal poles repel. On the one hand, there are permanent magnets, which are based on the interplay of elementary particles. On the other, magnetic fields also arise every time an electric charge is moved. To amplify the electromagnetism in play, the current-carrying conductor in an electric motor is arranged to form a coil. Electromagnets and – depending on the design of the motor – permanent magnets are arranged on two components. The stationary part is called the stator, the rotating part is the rotor, which turns when attractive and replusive forces are generated by periodically switching the electrical voltage on and off.

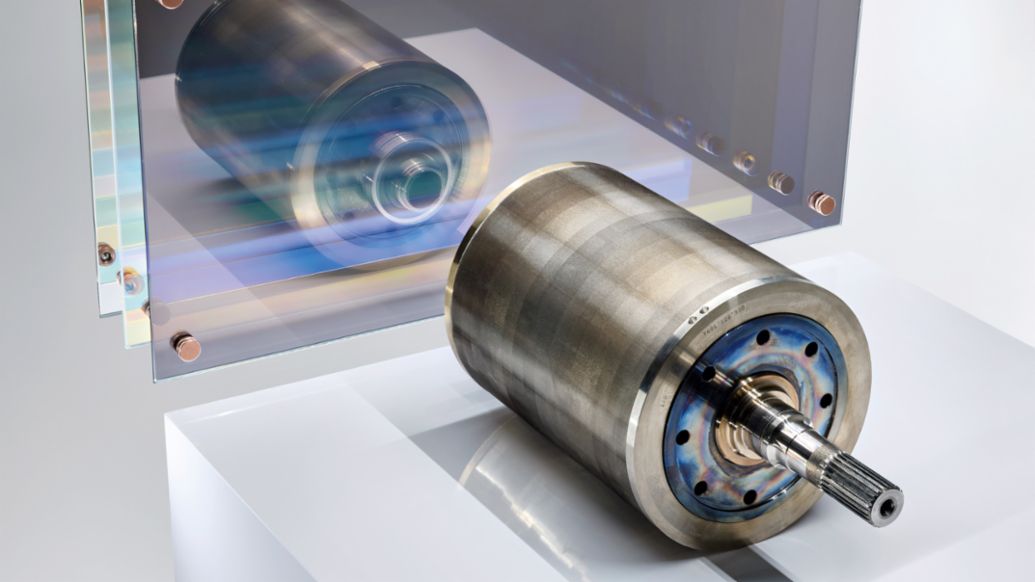

PSM instead of ASM

Not every type of electric motor is suitable for propelling a vehicle. Porsche makes use of the permanently excited synchronous machine (PSM). Compared to the predominantly used design – the cheaper asynchronous machine (ASM) – the PSM offers higher continuous output because it overheats less easily and therefore does not have to be turned down. Porsche’s PSM is supplied and controlled via power electronics with three-phase AC voltage: the speed of the motor is determined by the frequency at which the alternating voltage oscillates around the zero point from plus to minus. In Taycan motors, the pulse inverter sets the frequency of the rotating field in the stator, thereby regulating the speed of the rotor.

The rotor contains high-quality permanent magnets with neodymium-iron-boron alloys that are permanently magnetised during the manufacturing process via a strong directional magnetic field. The permanent magnets also enable a very high degree of energy recovery through recuperation during braking. In overrun mode, the electric motor goes into regenerative mode while the magnets induce voltage and current into the stator winding. The recuperation performance of the Porsche e-motor is the best among the competition.

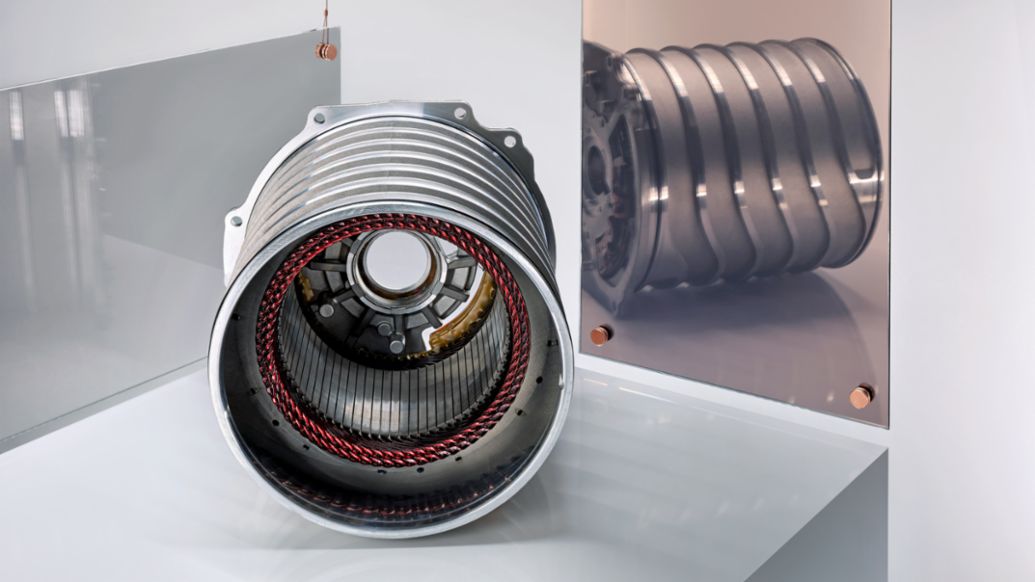

Hairpin winding: a special feature of the Taycan motors

Technology driven to its very limits: this Porsche gene is reflected in a special feature of the Taycan motors, known as the hairpin winding. Here, the coils of the stator consist of wires that are not round but rectangular. And unlike classic winding processes where the copper wire is obtained from an endless reel, hairpin technology is what is known as a forming-based assembly process. This means that the rectangular copper wire is divided into individual sections and bent into a U-shape, similar to a hairpin. These individual ‘hairpins’ are inserted into the stator laminations in which the winding is mounted in such a way that the surfaces of the rectangular cross-section lie on top of each other.

This is the decisive advantage offered by hairpin technology: it allows the wires to be packed more densely, thereby adding more copper to the stator. While conventional winding methods have a copper fill factor – as it is known – of around 50 per cent, the technology used by Porsche has a fill factor of almost 70 per cent. This increases power and torque with the same installation space. The ends of the wire hairpins are welded together by laser, creating the coil. Another important advantage is that the homogeneous contact between adjacent copper wires improves heat transfer and a hairpin stator can be cooled much more efficiently. Electric motors convert more than 90 per cent of the energy into propulsion. But just as in an internal combustion engine, the losses are converted into heat that has to be dissipated. That is why the motors have a cooling water jacket.

Culmination of Porsche expertise in the pulse inverter

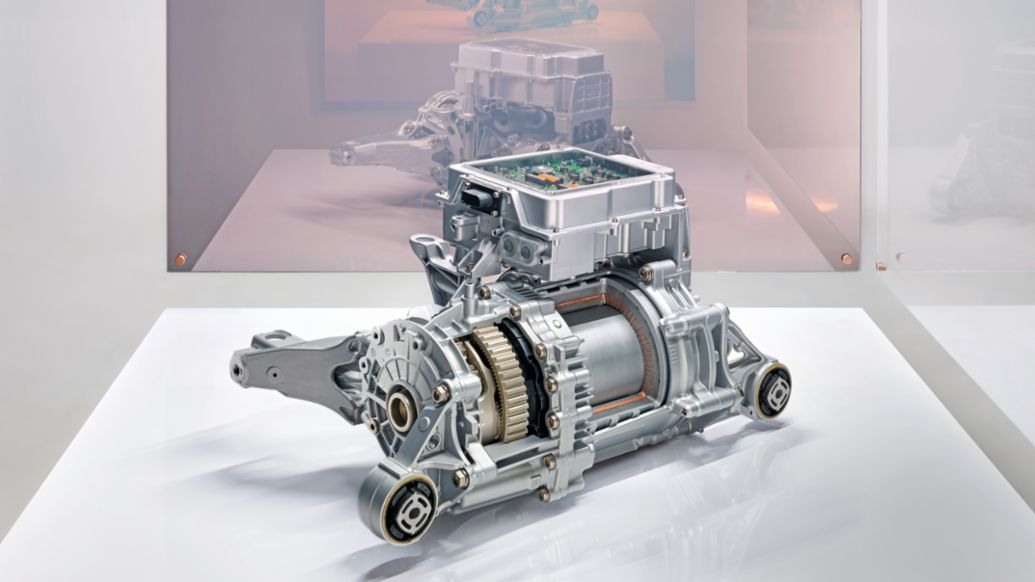

In order to precisely control a permanently excited synchronous motor, the power electronics must know the exact angular position of the rotor. This is what the resolver is for. It consists of a rotor disc made of field-conducting metal, an exciter coil, and two receiver coils. The exciter coil generates a magnetic field that is transmitted via the encoder to the receiving windings. This induces a voltage in the receiving coils, the phase position of which are shifted proportionally to the rotor position. The control system can use this information to calculate the exact angular position of the rotor. This control system, known as the pulse inverter, is the culmination of Porsche expertise. It is responsible for converting the battery direct current at 800 volts into alternating current and supplying it to the two e-motors.

Porsche was the first manufacturer to implement a voltage level of 800 volts. Originally developed for the Porsche 919 Hybrid race car, this voltage now reduces weight and installation space in series production thanks to leaner cables, enabling shorter charging times. The electric motors reach up to 16,000 revolutions per minute. To make optimum use of this speed range for Porsche’s signature spread between dynamics, efficiency and top speed, the front and rear drive units each have their own transmission. The Taycan is the first electric sports car ever to have a transmission with two shiftable gears on the rear axle, the first of which has a very short reduction ratio. On the front axle, an input planetary gearbox transmits power to the wheels.

These combine to give the Taycan Turbo S its mighty powers. At the front axle, the gear ratio translates the 440 Nm generated by the electric motor to around 3,000 Nm at the wheels. Some 610 Nm from the rear-axle motor are multiplied in first gear to about 9,000 Nm of axle torque. The task of the longer-ratio second gear is to ensure efficiency and power reserves at high speed. This is pioneering technology, applied to the smallest detail – and a continuation of Porsche’s tradition of innovation in the age of the electric drive.

Wednesday, March 17, 2021

The Geneva Motor Show: A Premier Venue for Mercedes-Benz and the 220SE Coupe (W 111)

Stuttgart. In the past, the Geneva Motor Show has always been a dazzling premiere venue for Mercedes-Benz. A look back over our shoulders brings back some very special memories: thus it was, 60 years ago, that the laid-back elegance of the 220 SE Coupé (W 111) thrilled the public. It was 30 years ago that the S-Class in model series 140 attracted the public eye in Geneva. In a less spectacular manner, but nevertheless of a high profile because of their tremendous utility value, two estate models aroused considerable attention 25 years ago: in 1996 Mercedes-Benz added a sporty estate variant (S 202) to the C-Class line-up of models for the first time. And the E-Class Estate (S 210) presented at the same time featured unrivaled spaciousness.

Mercedes-Benz 220 SE Coupé (W 111): In 1961, one of the most elegant coupés in the brand’s history was displayed at Lake Geneva. That luxurious two-door model – and together with it the cabriolet presented in autumn of the same year – was then built for eleven years with a range of different engine and transmission variants. Technically, the 220 SE Coupé was based on the “tail fin” saloon and, like the latter, was assigned the model series designation W 111. The unchanged floor assembly offered plenty of room for four seats and a large boot. However, the coupé’s body was 80 millimetres lower than that of the saloon, so only the radiator grille and the front light units could be carried over. The six-cylinder engine developed 88 kW (120 hp) from a displacement of 2.2 litres. The coupé and cabriolet are still coveted models today: the later versions with V8 engines, in particular, are amongst the most sought-after Mercedes-Benz classics.

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

Rule-Making and Rule-Breaking: Automobility and Film During a Decade of Constraints, 1970-1979

The Winners!

A Work-In-Progress

Rule-Making and Rule-Breaking: Automobility and Film During a Decade of Constraints, 1970-1979

By John Heitmann, Department of History, University of Dayton

Twenty years ago I considered the views of sociologist David Gartman as vulgar Marxism. But as I look at the post-World War II history of the automobile in America in 2021, I believe I was wrong. In his book Auto Opium, Gartman suggested that the two-toned, V-8 powered car of the era was nothing more than an opiate for hard-working Americans during the Cold War era. Accordingly, the automobile, no matter what model, was essentially the same. It served to lessen the rather harsh realities of a competitive capitalist system with its class structure, repetition, dehumanization, and repressive impulses. In short, it was at the heart of a “contradictory system.” It follows that during the 1950s, the car was a symbol and an expression of freedom at a time in American life when autonomy was in retreat. Freedom, then, was often quite illusory.

The automobile was also at the center of American notions of freedom. Journalist George Packer summed up the meaning of American freedoms in his acclaimed book The Unwinding as "freedom to go away, freedom to return, freedom to change your story, get your facts, get hired, get fired, get high, marry, divorce, go broke, begin again, start a business, have it both ways, take it to the limit, walk away from the ruins, succeed beyond your dreams and boast about it, fail abjectly, and try again." The automobile facilitated all that and more.

No discussion of freedom and the rebels that pursued that freedom during the 1950s could be complete without at least briefly mentioning Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957). The novel became one of the most important works of twentieth century literature and set the stage for innumerable travels and soul searching. A reflection of the social and cultural ferment of the early Cold War era, On the Road redirected the American road narrative as well. It is a story about a people on the margins of society – transients, disaffected intellectuals, farm laborers, and racial minorities. On the Roadalso takes us into the world of the 1950s that was far removed from middle class suburbia of the day – bop music, spontaneity, recklessness, drugs, and promiscuous sex. It seems unlikely, however, that Kerouac was just aiming in On the Road to describe a dark underworld populated by fascinating characters, the composite of which is one snapshot of America usually not taken. Certainly On the Road is infected with youthful optimism, far different from the negativity displayed in Henry Miller’s The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, or John Steinbeck’s The Wayward Bus. It also is far removed from the dark tale of a road trip gone bad, best exemplified in the classic 1945 film Detour.

Despite the institutional constraints placed upon Americans during the 1950s – by government, religious organizations, educators, community, and family -- the American automobile industry had virtually no countervailing power placed upon its exercise of autonomy. The industry’s first critics only surfaced in the late 1950s, and were largely ignored by the public, who had little options but to buy from the “Big Four,” led by General Motors. However, the early 1960s marked winds of change, the result of General Motors unconventional Corvair, and the efforts of a crusading lawyer convinced that the car was unsafe at any speed.

This is not the time to go into the Corvair or Ralph Nader stories, but to say that the result was the unleashing of a political and consumer firestorm that led to the federal government placing reigns on the industry for the first time. And perhaps rightfully so. In absolute numbers, traffic fatalities had risen from 34,763 in 1950, to 39,628 in 1956, to 53,041 in 1966, and 56,278 by 1972. During those years, the holidays between every Christmas and New Year resulted in the death of approximately 1,000 Americans. The rise of the interstate highway system beginning in 1956 and the marked increase in younger drivers contributed to the alarming trend. Design also played its part; along with horsepower gains, cars of the mid‑1960s often possessed poor handling characteristics and abysmal braking capabilities.

The seminal legislative action that set in motion strict automobile safety regulations was the 1966 National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. Beginning in 1968, this Act mandated that seatbelts, padded visors and dashboards, safety doors and hinges, impact absorbing steering columns, dual braking systems, and standard bumper height be installed in all new autos sold in the U.S. Push-back emerged immediately. Critics to these regulations, however, argued that these measures would do little to save lives and prevent injuries. History has proved them to be somewhat correct. Economist Sam Peltzman demonstrated in the mid-1970s that automobile safety devices resulted in “off-setting behavior” on the part of a number of motorists who engaged in more risky behavior as a result of the introduction of features that were designed to increase their chances of surviving a crash. And while seatbelts, soft interiors, and improved glass reduced driver fatalities, risky behavior increased the chance that a bicyclist or pedestrian would be killed or injured.

A second area where government had to step in and force manufacturers to take responsibility was the environment, particularly air pollution. Air pollution and haze first became an issue in Southern California, and it was California that first responded legislatively to the problem, with the federal government subsequently following the state’s lead. For years, manufacturers had claimed that devices to reduce the level of pollutants would take considerable time and research to develop. Industry’s hand was forced, however, in terms of technical feasibility, by the California legislature. In 1964 California certified four emissions control devices designed by aftermarket companies, and then mandated that devices of these types be installed on 1966 car models. In 1966, of an estimated 146 million tons of pollutants discharged into the atmosphere in the United States, some of 86 million tons could be attributed to the automobile.

As in the case of safety, a seminal federal act related to automobile emissions was passed and enacted in the mid-1960s, the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution and Control Act.30 This act set limits in terms of carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons, and was amended in 1971 to include evaporated gasoline. Additionally, the emissions stipulations in the Federal Clean Air Act (1970) further reduced allowable pollutants with the newly created Environmental Protection Agency as the enforcer.

In the wake of this legislation, however, Detroit responded shamelessly in terms of seriously tackling the issue. Rather than make substantial investments in a new generation of cleaner cars, the Big Three merely added aftermarket stopgaps to existing engines, thus minimizing their costs. In the process, they produced autos with very poor performance and drivability characteristics.

During the late 1960s and early 1970, Detroit manufacturers defied, circumvented, and publicly decried the new rules, and many Americans, including both auto enthusiasts and younger Americans did as well. Authority be damned, whether it be over illegal drugs, the Vietnam War and the Draft, policing methods, or speed. It was then that distrust in government heightened. Institutional controls gradually unwound, in part justified by Nixon administration lies and deception.

As younger Americans were taking to the road, there emerged a questioning as to whether the journey was a quest for self-knowledge or knowledge about others, and whether it was transformative or purposeless. It was in 1971, in the wake of the Kent State Shootings, the Attica Prison riots, blowing up or ROTC Buildings, the intensified bombing of North Vietnam, Mai Lai massacre, and increasing disillusionment, that two important road movies were released. Vanishing Point and Two Lane Blacktop. Vanishing Point featured as its hero an ex-Marine, Vietnam War veteran, policeman and motorbike racer Kowalski (Barry Newman). At the beginning of the film Kowalski has just arrived in Denver, and despite the offer to spend time with a prostitute, instead decides to take a deliver a fast Dodge Challenger in a return trip. As the jaunt unfolds in the vast spaces of the desert, we learn of the driver’s virtuous past through a series of flashbacks. Due to excessive speed, he becomes hunted by various State’s police as one might expect. But Kowalski has gained freedom for a time. Aided only by a blind black disc jockey named Super Soul (Cleavon Little), Kowalski is called “the last beautiful free soul on the planet.” Others who come to Kowalski’s aid include a black biker, two white hippies, and an old snake-catcher in a broken down car. All are individuals at the margins, like our hero, and like the primary characters in On the Road. As the road trip ends, as Kowalski accepts defeat, and rams his car into a police barricade.

While Vanishing Point was remade in the 1990s starring Vigo Mortenson as Kowalski, Monte Hellman’s Two Lane Blacktop, also released in 1971, has become a cult classic despite being a box-office flop. The film’s stars are nameless: the Driver (James Taylor), Mechanic (Dennis Wilson), G.T.O. (Warren Oates) and the Girl (Laurie Bird). Perhaps the unusual deaths of Wilson, Oates and Bird added to the mystique of this road movie to nowhere, where the characters are nameless, but the cars are listed in the cast as Chevrolet and Pontiac. The actors are largely silent, expressing themselves at times with facial expressions sensitively captured by Hellman. And the race is futile. Gratification is not forthcoming, echoed by The Girl who sings “I can’t get no satisfaction” while playing pinball.

One thing is undeniable about the influence of Two Lane Blacktop -- it fired the enthusiasm of journalist Brock Yates to organize a series of coast to coast speed trials in 1971 and 1972 called the Cannonball, or Sea-To-Shining Sea Memorial Trophy Dash. Yates had asked himself, “When was the last time Ayn Rand sent somebody on a cross-country motor race?” With eight contestants, Grand Prix Driver Dan Gurney, assisted by yates, won the first prize in a Ferrari with an elapsed time of 35 hours and fifty four minutes and average speed of 80 miles per hour. A second event was sponsored by Car and Driver in 1972, and this time the winners, Steve “Yogi”Behr and Bill Canfield, won in a Cadillac with a time of 37 hours sixteen minutes and an average speed of 78.04 mph.

Oil Shock I in 1973 served to separate the earlier two runs from the latter two in terms of the motives of these adventures – the 55 mile per hour national limit chaffed drivers more than any forced design modification or governmental edict. The oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 also did more to forcefully influence Detroit’s direction in the manufacture of more fuel-efficient automobiles than the federal government’s Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards and the 1978 Gas Guzzler Tax. Indeed, the shortage of petroleum products and the rise in the cost of gasoline, along with foreign competition, carried more weight in transforming automotive technologies than consumer demand or government regulation. And it emboldened government bureaucrats to flex their muscles, including Department of Transportation heads John Volpe, who had previously argued that government can do a better job of designing cars than the industry.

As early as 1971 Volpe lectured to auto enthusiasts in the magazine Motor Trend that

Actually, highway safety regulations do not violate a person’s right to a private life. Whenever a person drives a vehicle onto a public road, he leaves his private life behind him. Public roads belong to the State and the State can, indeed must, set appropriate standards regarding the use of those roads.

No man is an island unto himself when he is wheeling down a highway in a truck, an automobile, or a motorcycle. First of all he is a potential threat to anyone else using the same roadway – or along it if he should leave the roadway out of control. Secondly, if he has an accident, even if he is the only one hurt, it is going to cost the State money.…

A 55 mile-per-hour national speed limit, the result of Oil Shock I, was undoubtedly the most significant federal mandate effecting everyday life of drivers after 1973. The National Maximum Speed Law, a provision of the Federal Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act, took the authority of speed limits out of the hands of the states and remained in force until 1995. The intent of the law was to both save lives and reduce gasoline consumption. Loss of life from the measure proved minimal at best, according to Stephen Moore at the Cato Institute. The overall consumption results also proved disappointing; while it was projected that the national demand for gasoline would drop by 2.2%, it is estimated that it achieved saving only between .5 and 1%.

Many Americans both hated and defied the 55-mile-per-hour limit. Two technologies emerged during the 1970s to help circumvent ‘Smokey’ and his speed traps and radar guns. Citizens band (CB) radios were first used by truckers, and then by passenger car owners. CB radio users had individual ‘handles,’ or catchy names, that suggested one’s individuality and values.

Drivers unhappy with the “double nickel” speed limit also created a mass market for radar detectors. Beginning in the early 1950s, police effectively used Doppler-effect radar systems to keep down speeds on busy highways, and reduce alarming fatality rates. The American Automobile Association denounced the use of these devices, and drivers tried to scramble signals by putting tin foil and steel marbles in their hubcaps, only to be charged with obstruction of justice if caught.

In 1955 more than 20% of all speeding arrests were achieved by radar, with conviction rates between 90-100%. Radar detectors were soon built by electronic hobbyists, perhaps the most famous being John Davis Williams, a RAND Corporation scientist who had expertise in statistical radar detection for military applications. In 1958 the amateur radio magazine CQ published an article entitled “Radio Speedmeter Receiver.” The technology for that device was ingeniously modified to create the first commercially available radar detector, the Radatron Radar Sentry, that was featured on the cover of Popular Electronics in September, 1961. The Radar Sentry remained in the marketplace until the early 1970s. It was later made obsolete by a host of competitors with names like Fuzzbuster, Bearfinder, Road Patrol, Wawassee Alley Cat, Snooper, and Whistler. The best perhaps, was the Electrolert Fuzzbuster, developed by Dale T. Smith. Incensed over a speeding ticket, Smith designed, and then promoted, the best radar detector of that day. Further, he proved to be an effective lobbyist for the devices, arguing that American citizens have a right to know when they are being watched electronically, even as they drive.

With the national speed limit set at 55, Car and Driver magazine called for entries set for a Cannonball start on April 23, 1975. With 18 entrants, Jack May and Rick Cline took the prize in a 1973 Ferrari Dino 246GTS and a time of 35:53. In addition to the Ferrari, the contest featured a Dodge Challenger, Mercedes 450 SL, Porsche 911 RSR, a 1975 Buick Electra, and a very unlikely1951 Studebaker. The race was featured on the cover of the August issue of Time, andHollywood was quick to follow with Cannonball, and Gumball Rally. Cannonball, starring David Carradine, was a hastily pieced together film, with sloppy cinematography, bland landscapes, poor character development, and for the most part unremarkable vehicles. The Gumball Rally, however, proved to be the best of the lot of these coast-to-coast films. With a relatively undistinguished cast led by Michael Sarrazin, Susan Flannery, and Gary Busy, it the cars and their sounds – a Cobra, Ferrari, Porsche 911 Targa, Mercedes 300 SL and Rolls-Royce that emerged as the stars, along with wonderful road scenes and landscapes. It is a film still worth watching.

A final bash took place in 1979, with the winners finishing in an elapsed time of 32:51 driving a 1978 Jaguar XJS. A 1984 Hal Needham directed film entitled Cannonball Run followed. It proved to be a corny and tiresome picture that demonstrated how no matter how many stars are featured -- including Burt Reynolds, Dom De Luise, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Jamie Farr, Ricardo Montalban, Telly Savalas, Shirley MacClain, Jackie Chan, Tim Conway, and Don Knotts -- a bad script can relegate the work to the level of crap. Roger Ebert gave the film half a star out of four, calling it "one of the laziest insults to the intelligence of moviegoers that I can remember. Gene Siskel also gave a harsh review of this film, calling it "a total ripoff, a deceptive film - that gives movies a bad name."

Similar films from the 1970s that did not follow the Cannonball formula, but promoted a general defiance toward authorities and a celebration of autonomy and freedom. The best were Convoy and Smokey and the Bandit. The regional center of these speed limit defiant films was attributed to the Deep South, ironic in a way since it was by far the most conservative of all regions in America. In the case of Smokey and the Bandit the iconic car of the 1970s became the 1977 Pontiac Firebird Trans-Am.