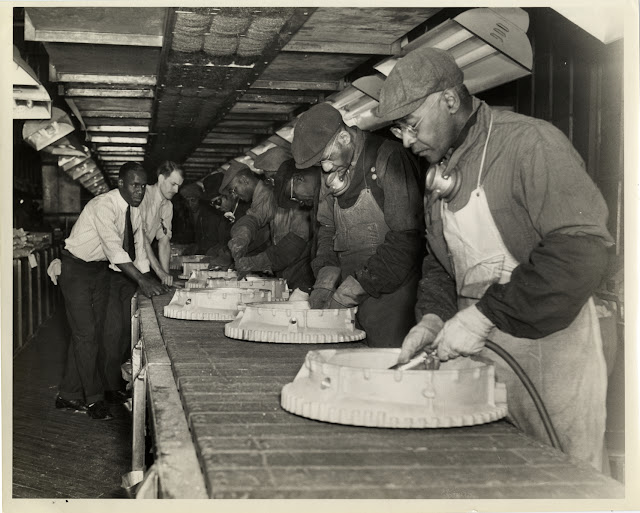

images from Detroit Public Library Digital Collections

The Independents

To place the entire focus of the

discussion on Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler would distort the nature of

the automobile industry’s history during the 1920s, for there were many other

automobile manufacturers during the decade. The industry was not quite yet

mature, and consequently entry was still possible, and a number of marques were

both innovative and popular. A shakeout would take place with the onset of the

Great Depression, but even during the grim 1930s a number of smaller prodders

hung on. The following chart lists a number of American car manufacturers44,

although two electric car manufacturers – Detroit and Rauch & Lang, are

excluded.

|

Auburn |

Franklin |

Peerless |

|

Buick |

Gardner |

Pierce Arrow |

|

Cadillac |

Hertz |

Pontiac |

|

Case |

Hudson |

Reo |

|

Chandler |

Hupmobile |

Rickenbacker |

|

Chevrolet |

Jordan |

Roamer |

|

Chrysler |

Kleiber |

Rolls Royce |

|

Cunningham |

Lincoln |

Star |

|

Davis |

Locomobile |

Stearns |

|

Diana |

Marmon |

Studebaker |

|

Dodge Brothers |

McFarlan |

Stutz |

|

DuPont |

Moon |

Vehie |

|

Elcar |

Nash |

Wills St. Clair |

|

Erskine |

Oakland |

Willis Knight |

|

Essex |

Oldsmobile |

|

|

Falcon-Knight |

Overland |

|

|

Flint |

Packard |

|

|

Ford |

Paige |

|

Given the complexity of the

automobile market during the 1920s, it is impossible here to discuss the

corporate histories of each of these firms. However, case studies of a few of

these “orphan” marques may be instructive.

Innovation

at the Periphery: The Cracker Jacker,

Rickenbacker

View of Eddie Rickenbacker posing with Rickenbacker car. Two unidentified men sit in car; spectators watch from grandstand in background. "AAA Contest Board" painted on side of car

The Rickenbacker automobile,

advertised as “a car worthy of its name,” was manufactured in Detroit between

1921 and 1927.45 Named after Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, America’s

“ace of aces” during World War I and the commander of the “Hat in the Ring”

squadron, the Rickenbacker was designed along the lines outlined by former auto

racer “Captain Eddie’s” specifications. In 1919 Rickenbacker decided that he

would build a car that incorporated such race-proven advanced features as a

rigid frame, 4-wheel brakes, and a high standard of construction. Envisioned as

fitting in the market somewhere between the low-end Ford Model T and the far

higher priced Cadillac and Packard, it was to be affordable to white-collar

workers, prosperous farmers, and “women of taste.”

Rickenbacker sold his ideas to

Maxwell executive Harry L. Cunningham, who subsequently recruited an impressive

management team. Among the new firm’s executives were coach builder Barney F.

Everitt and Walter E. Flanders, formerly the production manager at Ford. With

Cunningham as Secretary and Treasurer and Rickenbacker as Vice President and

Sales Manager, the Rickenbacker Motor Company was initially well positioned.

During 1921 a six-cylinder prototype

was built and tested, $5 million worth of stock was sold, and a plant with a

12,000 unit capacity was acquired. Three Rickenbacker models debuted in 1922 –

a Tourer, Opera Coupe, and Closed Sedan – and more than 3,700 cars were sold,

resulting in a 5 percent stock dividend.

Rickenbacker six- and eight-cylinder

models gained a reputation for innovative technology and enhanced safety

features. For example, while not the first American automobile to offer 4-wheel

brakes, the Rickenbacker was the first moderately-priced car to do so. Other

advances not found in less expensive models included a low vibration flywheel

engine, ignition and transmission locks, and an ingenious system to purify

engine oil and avoid crankcase dilution, a carburetor air cleaner, and

automatic windshield washer. The proud owner of a Rickenbacker could sing along

to the popular tune “Merrily I roll along and there’s nothing

wrong . . . in my cracker jacker, Rickenbacker.”46

But in fact storm clouds soon passed

over the fledgling firm, and it began to experience production and financial

difficulties. By then, Walter Flanders had died the result of an unfortunate

accident. Handicapped with small profit margins, Everitt cut prices without

consulting dealers and stockholders. Marginal dealers went bankrupt,

stockholders and management squabbled, and in 1926 Captain Eddie resigned.

Everitt was now on his own and on borrowed time, and the company closed its

doors in February 1927. Its machinery and engines were later sold to German

industrialist J. A. Rassmussen, who used Rickenbacker engines in his Audi

Dresden Sixes and Zwickau Eights between 1928 and 1932.

Like the Richelieu, Saxon, Dort,

Flint, Winton, King Jewett, Wills Ste. Clair and numerous other Midwestern

automobile companies, the Rickenbacker could not survive competition from more

highly capitalized and cost-efficient firms, even during America’s prosperity

decade of the 1920s.

The

Jordan and Advertising the Dream

Advertisement for Jordan cars from the Saturday Evening Post. Text reads: "Somewhere west of Laramie. Somewhere west of Laramie there's a broncho-busting, steer-roping girl who knows what I'm talking about. She can tell what a sassy pony, that's a cross between greased lightning and the place where it hits, can do with eleven hundred pounds of steel and action when he's going high, wide and handsome. The truth is -- the Playboy was built for her. Built for the lass whose face is brown with the sun when the day is one of revel and romp and race. She loves the cross of the wild and the tame. There's a savor of links about that car -- of laughter and lilt and light -- a hint of old loves -- and saddle and quirt. It's a brawny thing -- yet a graceful thing for the sweep o' the Avenue. Step into the Playboy when the hour grows dull with things gone dead and stale. Then start for the land of real living with the spirit of the lass who rides, lean and rangy, into the red horizon of a Wyoming twilight. Jordan Motor Car Company, Inc. Cleveland, Ohio." Typed on front: "Edward S. Jordan."

View of 1930 Jordan car in showroom. "Jordan" sign on back wall. Stamped on back: "Lazarnick, photographic illustrations, 230 Park Avenue, New York Central Building, New York City, Tel. Vanderbilt 3-0011-2-3-4." Handwritten on back: "Jordan, 1930."

The Jordan automobile presents a

different story but with a similar ending. The Jordon was the result of the

vision and energy of Edward S. “Ned” Jordan. Born in 1881 and educated at the

University of Wisconsin, Jordan’s career included a stint in advertising at the

National Cash Register Company in Dayton and in a similar position with the

Jeffery Automobile Company, located in Kenosha, Wisconsin. In 1916, Jordan

organized his own automobile company, located in Cleveland, Ohio, with the idea

that the firm’s vehicles would manufacture cars that cost not quite as much as

a Cadillac but more than a Buick. Always relatively expensive and assembled

from parts, engines, and bodies made elsewhere, about 80,000 units were sold

between 1916 and 1931. Normally priced over $2,000, the Jordan was marketed at

the well-to-do.

The Jordon was noteworthy for

several reasons. Ned Jordan had an uncanny understanding of well-to-do American

consumers from the point of view of color, and from the firm’s origins, his

cars could be ordered in a number of unusual shades, long before the color

revolution of the late 1920s. Thus, as early as 1917 Jordan cars could be

purchased in colors such as Liberty Blue, Pershing Gray, Italian Tan, Jordan

Maroon, Mercedes Red, and Venetian Green. And when the “True Blue” Oakland was

introduced in 1923, Jordan quickly followed with its 1923 Blue Boy model.

Secondly, Jordan understood the post-WWI youth market and responded with the

marque’s most famous model, the Playboy. Supposedly, the Playboy idea was the

result of Ned’s dance with a 19-year old Philadelphia socialite, who quipped,

“Mr. Jordan, why don’t you build a car for the girl who loves to swim, paddle

and shoot and for the boy who loves the roar of a cut out?”47 Ned

would later refer to this as a million dollar idea, and the Playboy was born.

Finally, Jordan was a flamboyant advertising copywriter, and it would be in his

Playboy ad copy written in 1923, “Somewhere West of Laramie,” that American

automobile advertising would be transformed.

While there is little doubt that twentieth century advertisements serve

as important cultural documents, there is considerable debate as to their

meaning.48 In his Understanding Media (1964), Marshall

McLuhan asserted that “historians . . . will one day

discover that the ads of our times are the richest and most faithful daily

reflections that any society ever made of its entire range of activities.” This

is especially true in a capitalist economy, where consumption and persuasion

are so important. Raymond Williams insightfully labeled advertising as

capitalism’s “official art.” With regard to advertising, the work of Judith

Williamson, Roland Marchand and William O’Barr all significantly contribute to

an understanding of its meaning. Williamson’s Decoding Advertisements:

Ideology and Meaning in Advertising provides the reader with a step-by-step

guide in the dissection of an advertisement. Marchand’s Advertising the

American Dream: Making Way for Modernity is a powerful example of how a

cultural historian can employ advertising to reconstruct the past. And O’

Barr’s work, while primarily aimed at using advertising to illuminate

discursive themes in social history that include hierarchy, power,

relationships, and dominance, has an excellent synthetic theoretical

introduction. O’Barr follows along the lines of Marchand in arguing that social

and cultural values appearing in advertisements are more a refraction than a

representation. The two scholars also agree that audience response, while important

to copywriters, is beyond the scope of the historian, and at any rate

problematic. Past audience responses are simply impossible to accurately

reconstruct. In the present, there is no simple way to ascertain meaning, for

meaning involves the interplay of the naive with the critical, and thus there

is an ultimate variance among interpreters. The problems associated with the

use of advertising, however, can be extended to many, if not all of the various

manuscript, textual, visual, and oral sources used by the historian.

In the early days of automobile

advertising, the features of an automobile were often emphasized. For example

an ad for the new 1917 seven passenger Oldsmobile claimed that

This light weight, eight cylinder

car combines power, acceleration, speed, economy, comfort, beauty, and luxury

in a measure hitherto undreamed of in alight car. The eight-cylinder motor,

developing 58 horsepower at 2,6000 r.p.m., with the light weight of the car –

3,000 pounds – presents a proportion of power to total car weight of

approximately one horsepower to every 51 pounds – an unusually favorable ratio.

The comfort of the car is beyond description. Long, flat, flexible springs and

perfect balance of chassis insure easy riding under any kind of going. The seats,

upholstered with fine, long grain French leather stuffed with pliant springs

encased in linen sacks, increase comfort to the point of luxury.

This style of advertising was swept

aside by the mid-1920s. In 1923, Edward S. Jordan created the most famous auto

ad of all time to move his colorful Playboy Roadsters.49 Jordan had

a gift for writing advertising copy; in 1920 a Playboy ad suggested a visit to a local bordello:

Somewhere far beyond the place where

man and motors race through canyons of the town – there lies the Port of

Missing Men.

It may be in the valley of our

dreams of youth, or the heights of future happy days.

Go there in November when logs are

blazing in the grate. Go there in a Jordan Playboy if you love the spirit of

youth.

Escape the drab of dull winter’s

coming – leave the roar of city streets and spend an hour in Eldorado.50

While traveling on a train across

the flat and monotonous Wyoming plains, a tall, tan, and athletic horsewoman

suddenly appeared, racing her horse toward Jordan’s window. For a brief moment

the two were rather close as the woman smiled at him; then she turned and was

gone. Jordan asked a fellow traveler where they were: “Oh, somewhere west of

Laramie,” was the desultory reply. Within minutes he composed an immortal ad

that later appeared in the Saturday Evening Post. Beneath an

illustration of a cowgirl racing a sporty Jordan roadster against a cowboy

straining to push his fleet-looking steed to catch up with her, there appeared

these words:

Somewhere

west of Laramie there’s a bronco-busting, steer roping girl who knows what I am

talking about. She can tell what a sassy pony, that’s a cross between greased

lightning and the place where it hits, can do with eleven hundred pounds of

steel and action when he’s going high, wide and handsome.

The

truth is the Playboy was built for her.

Built

for the lass whose face is brown with the sun when the day is done of revel and

romp and race.

Step

into the Playboy when the hour grows dull with things gone dead and stale.

Then

start for the land of real living with the spirit of the lass who rides, lean

and rangy, into the red horizon of a Wyoming twilight.

The Playboy sold

like hot cakes, and this ad galvanized the auto industry. Soon Chevrolet and

Rickenbacker responded with ad lines “All outdoors can be yours,” and “The

American Beauty,” respectively.51

Previously ads mentioned the

features of the car, but with the Jordan ad new parameters came into play –

freedom, speed, and romance. Emblematic was the fact that the practical Model

T's life had come to an end. Now it would be art and color that was the key to

auto sales.

The

prosperity decade of the 1920s resulted in a remarkable restructuring of the

American automobile industry and a drive towards consolidation as numerous

small manufacturers dropped out of the marketplace. Given the drive towards

efficiencies in production and distribution, intense pressures were placed not

only on the workmen who assembled the cars, but also the consumers who bought

them, increasingly on credit and after being exposed to more subtle and

suggestive advertising. With more wealth and disposable income, consumers

wanted more – more horsepower, more size, more colors and style, and more

conveniences. The automobile was now an object of desire among all classes of

Americans, and as such it transformed our personal and social habits, as well

as the road and roadside.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)