This blog will expand on themes and topics first mentioned in my book, "The Automobile and American Life." I hope to comment on recent developments in the automobile industry, reviews of my readings on the history of the automobile, drafts of my new work, contributions from friends, descriptions of the museums and car shows I attend and anything else relevant. Copyright 2009-2020, by the author.

Saturday, February 24, 2024

Stealing Freedom: A History of Automobile Theft, My Webinar, February 15, 2024

Thanks to the folks at the Canadian Automotive Museum for inviting me to do this!

Wednesday, February 14, 2024

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

Waymo Car Vandalized in San Francisco -- Resentment Towards AI and Autonomous Cars? Will the Luddites Finally Rise?

No car wirh a driver would be at this intersection at this time, but the Waymo Car did not know that. And so it headed into a Lunar New Year celebration and was vandalized by a crowd perhaps not so sympathetic to high tech and capitalism. When will society turn on all the new technology that we are exposed to? When will the Luddites rise and take back the planet?

Sunday, February 11, 2024

Technological Countermeasures to Automobile Theft Invented and at Times Used during the 1920s

Between 1914 and 1925 there were at least 25 patents related to a wheel chock or wheel lock that shackled a wood spoke wheel. Of course, a would-be thief only had to take off the wheel to defeat the device.

Technological Countermeasures

Beyond commonsense precautions, automobile owners were advised to take preventive measures to stop early car thieves. Perhaps the most bizarre, and in retrospect, humorous countermeasure was the Bosco "Collapsible Rubber Driver." Made in Akron, Ohio, ad copy for the rubber man claimed that "locks may be picked or jimmied. Cars may be stolen in spite of them. But no thief ever attempted to steal a car with a man at the wheel. [It] is so lifelike and terrifying, that nobody a foot away can tell it isn't a real, live man. When not in use, this marvelous device is simply deflated and put under the seat."[1]

Owners were advised to lock their doors or “garage” their automobiles. In his 1917 article “Automobile Thefts,” John Brennan proposed another counter-measure: “If owners would only take steps to put private identification marks on their cars, the problem of automobile thievery would be a simple one to solve.”[2] It was suggested that the owner bore holes into the underside of the running boards, scratch their name somewhere secret, or tape an identification card inside the upholstery.[3]

In addition to leaving a secret mark or set of identification marks, stronger locking mechanisms were proposed. One such deterrent, first marketed in 1920, was the Simplex Theftproof Auto Lock.[4] Advertised with the moniker "To be simple is to be great," the device appeared to be a simple collar lock, made of bronze and steel, and installed in twenty minutes by a mechanic. Once in place the Simplex lock positioned a vehicle's front wheels straight ahead, and it was claimed that such a vehicle could not be towed. Available in five diameters, the anti-theft collar could be attached to virtually every American car, and at the modest cost of $15, not including professional installation.

A far more effective and popular locking device marketed and installed during the 1920s was the Hershey Coincidental Lock. In a 1928 advertisement in The Saturday Evening Post, its manufacturer asked the question "Will your NEW car be safe?" The ad copy argued their product -- with more than 2 million sold -- locked "not only the ignition, but the steering as well -- with a hardened steel bolt."[5] The Hershey Coincidental Lock was the work of inventor Orville S. Hershey and Ernest J. Van Sickel, both from Chicago.[6] First developed in the early 1920s and then refined during the remainder of the decade, the lock anticipated steering wheel locks that were mandated by the federal government in the 1970s, and indeed was perhaps stronger than the locks that appeared on Big Three cars at that later date. With a combination ignition cut off and strongly reinforced deadbolt, the owner of a Hershey automobile lock could opt to disable the deadbolt and only secure the car by switching off the ignition, or one could employ both deterrents if so desired.

One might hastily conclude that manufacturers had little interest in selling automobiles that had secure locking systems, but that would be wrong. It is difficult to generalize on the matter of Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) ignition locks installed on cars from the 1920s to the 1930s. Changes took place year to year in terms of supplier, design, and placement. For example, for a time in 1932 and then later, V-8 Fords sometimes had a lock on the transmission, other times on the steering column.[7] By the mid-1930s General Motors had settled on a disk or wafer tumbler design, based on that developed by Briggs and Stratton. This lock featured six wafers (pins were also used in some cases) and a single-sided key. If the proper key was inserted, the wafers were moved so that the core or plug of the lock could freely rotate. However, if there was no key or the wrong key in the cylinder, the wafers were not aligned with the so-called lock shear line, and the cylinder core remained fixed.[8]

However, no matter how intricate, locks were invariably defeated by the experienced thief, either by bumping or picking, or simply cutting or forcing open. Another approach tried in the 1920s was to provide a visible identification number and set of authorized driver photographs. Such was the product marketed by the Auto-Thief-Stopper Company of Detroit, Michigan. The invention of Wallace C.D. Cochran in 1922, the "STOP THE THIEF" plate was secured to the motor vehicle's gas tank.[9] The information on the specially embossed and sealed card included a "Whizzer" serial number, photographs of owners and authorized drivers, their addresses, and information on the color of hair and eyes, complexion, and distinctive marks that might include birthmarks and scars. The basic notion was that service station attendants would check the plate before servicing the car, and "if any doubt arises, hold parties and summon an officer." If one attempted to remove the plate, the result would be a hole in the gas tank; to alter the plate would break seals that could not be repaired. However, there does not exist in the historical record any evidence that such an identification card ever caught on during the 1920s. But the plate did reflect one of the most important shortcomings of the automobile of the 1920s, namely that a uniform system of vehicle identification numbers did not exist, and that stamped numbers on the motor or chassis were easily altered.

Perhaps the most significant anti-theft technological system introduced during the 1920s, aimed at owners and manufacturers was the FEDCO number plate. According to one company brochure, the FEDCO System was a response to the utter failure of any method to arrest the alarming increase in auto thefts during the mid-1920s.[10]

New York City-based FEDCO (Federated Engineers Development Corporation) was a firm "devoted to the complete, practical development of inventions." Beginning in 1923 it had worked on an anti-theft number plate with the Society of Automotive Engineers, the Underwriters Laboratories, and the Burns International Detective Agency. Essentially FEDCO metallurgists fabricated a plate that self destructed when one attempted to remove or alter it. With digits made of white metal and standing out behind a background of oxidized copper, the entire plate also had an embossed surface that was characteristic of the car make. Below the numbers the digits were spelled out, and this complex identifier proved to perplex those who tried to foil it. The idea behind the FEDCO System, then, was based on a number plate attached to the dashboard of a new car coming off the assembly line. To alter or remove the plate would result in its destruction, leaving a tell-tale remnant, indicative of tampering. And apparently the technology worked, at least according to one car thief who was caught as a result of it. Writing his confession from the Nassau County, New York jail, auto thief A.M. Bachmeyer exclaimed that "had I realized just what this number plate meant I would not have stolen this car."[11] While the FEDCO system proved to be an effective deterrent, there is no evidence that Chrysler continued with the number plate after 1926, or that other manufacturers adopted the unique plate technology.[12]

[1] Floyd Clymer, Historical Scrapbook No. 4 (Los Angeles: Clymer, 1947), p. 162.

[2]Ibid., p. 565.

[3] “How Safe Is Your Automobile?,” p. 532.

[4] Simplex Corporation, Chicago, "Simplex Theftproof Auto Lock: A Look for Every Car," Trade Catalog Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn, MI.

[5] Ad for Hershey Coincidental Locks, Saturday Evening Post, May 19, 1928, 50.

[6] See Orville S. Hershey, "Automobile Lock," U.S. Patent 1,685, 128, September 25, 1928; ; Orville S. Hershey, "Automobile Lock," U.S. Patent 1,694,506, December 11, 1928; E.J. Van Sickel, "Automobile Lock," U.S. Patent 1,730,396, October 8, 1929.

[7] Edward P. Francis and George De Angeles, The Early Ford V8 as Henry Built It (South Lyon, MI: Motor Cities Publishing, 1982), p. 53.

[8] Stephen F. Briggs, "Lock," U.S. Patent 1,826,649, October 6, 1931. Robert F. Mangine, "Examination of Steering Columns and Ignition Locks," in Eric Stauffer and Monica S. Bonfanti, Forensic Investigation of Stolen-Recovered and Other Crime-Related Vehicles (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006), pp. 227-258.

[9] Wallace C.D. Cochran, "Opportunity: A pamphlet Addressed to Capital, and Pointing the Way to the Establishment of a Gigantic New Business Enterprise, VIZ: -- Wholesale Automobile Theft Insurance, with the Risk Eliminated." October 9, 1922. Vertical File, Theft Prevention, National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library.

[10] Fedco Number Plate Corporation, "Foiling the Auto Thief: The FEDCO System of Automobile Theft Prevention and Detection," December, 1927, Vertical File, "Theft Protection," National Historical Automobile Collection, Detroit Public Library.

[11] Ibid., n.p.

[12] The relationship between Chrysler and Fedco apparently ended after the 1926 model year. See Thomas S. LaMarre, “From Model B to Big Three: Chrysler’s Amazing Ascent,” Automobile Quarterly, 32, no. 4 (1996), 25.

Saturday, February 10, 2024

Friday, February 9, 2024

Automobile Theft and the 1920s American City Scene

Automobile Theft and the 1920s City Scene

By the 1920s, Automobile

theft was most acute in Detroit and Los Angeles. “Naturally Detroit is

peculiarly liable to this trouble because it has such a large floating

population of men trained to mechanical expertise in the various factories.”[1] It stood

to reason that Ford’s workers stole Ford’s cars. Arthur Evans Wood reported that in 1928 in

Detroit a total of 11,259 cars were stolen.[2] Of those thefts less than 10 percent led to

an eventual arrest, and only 50 percent of that group was ever prosecuted. In the end, only 25 percent of those persons

arrested for auto theft in this particular group were ever convicted. Since at that time many thieves ended up

paying off "coppers" to avoid apprehension, one might conclude that this

crime actually did pay.

The same year in Los Angeles 10,813

automobiles were stolen.[3] By the

1920s, Los Angeles had the most automobiles per resident in the United States.

And this fact clearly was changing the face of crime in the City of Angels. Historian Scott Bottles has pointed out that

“By 1925, every other Angelino owned an automobile as opposed to the rest of

the country where there was only one car for every six people.”[4] Angelinos

had more opportunities to steal cars, and some took those opportunities. In 1916 some 1,300 cars were stolen and 85%

were recovered; a decade later more than 10,000 were taken with an 89% recovery

rate.[5] Theft statistics remained in the range

between 5,000 and 8,000 cars per year to the onset of World War II.

Baltimore, New York City, Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, Omaha, St.

Louis, and many other cities also experienced major problems related to

automobile theft. In 1918, the year

immediately before federal legislation was enacted to stem the auto theft tide,

Chicago experienced more than 2,600 thefts; St. Louis 2,241; Kansas City 1,144;

and Cleveland, 2,076. [6] However, in an article

published in Country Life, Alexander

Johnson revealed the problem was not just endemic to urban America: “We who

live in the country are not quite as subject as our urban brethren to this

abominable outrage, but automobile stealing is carried on even in the rural

districts.”[7] Although cars from the countryside certainly

were stolen from time to time, auto theft remained largely an urban problem

from the WWI era to this day. Joy riders

could be found in every locale; gangs, rings, bootleggers, and drugs were very

much a part of the city scene.

Of course,

within each city there were some neighborhoods that were more secure than

others. And there were "hot spots," some of which were connected with

the race of the majority of their inhabitants.

Such was the case of Chicago in the early 1930s, where in several

red-lined districts insurance underwriters refused to issue policies

"except under special arrangement." In these African-American neighborhoods

"conditions are so deplorable …that resident motorists cannot obtain any

insurance." To clarify its reasons for making such a decision, the

insurance industry stated that "The reason that Negros cannot secure theft

insurance is not one of discrimination, but more or less one of character.

Color does not play any part."[8]

Vehicles Stolen

in Buffalo, New York Between 15 May and 15 July 1924

Make of Motor Vehicle Number

Auburn 2

Buick 26

Cadillac 5

Chevrolet 61

Chalmers 1

Chandler 1

Cole 2

Dodge 8

Dort 1

Durant 4

Elcar 1

Essex 1

Ford 172

Franklin 3

Gardner 1

Haynes 4

Holmes 2

Hudson 7

Hupmobile 1

Jewett 2

Jordan 5

Marmon 3

Maxwell 5

Moon 1

Nash 7

Oakland 3

Oldsmobile 3

Overland 15

Packard 2

Paige 1

Peerless 2

Star 1

Stearns-Knight 2

Studebaker 10

Velie 2

Wills St. Claire 5

Willys Knight 5

(Source: "Automobile Record Book for 1924," Buff)alo,

New York

[1] Johnson, “Stop Thief!,” 72.

[2]

Bennet Mead, “Police Statistics.” Annals

of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 146 (Nov. 1929),

94. Arthur Evans Wood, "A Study of Arrests in Detroit, 1913 to 1919,"

Journal of the American Institute of

Criminal Law and Criminology, 21 (August, 1930), 99.

[3]Wood,

p.94.

[4]

Scott Bottles, Los Angeles and the

Automobile: The Making of a Modern City (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1987),

p. 92.

[5]

J.B. Thomas, Conspicuous Depredation:

Automobile Theft in Los Angeles, 1904-1987 (N.P.: Office of the Attorney

General, California Department of Justice, Division of Law Enforcement,

Criminal Identification and Information Branch, Bureau of Criminal Statistics

and Special Services, March 1990).

[6]

US House of Representatives, 66th Congress, 1st

session, Report 312: Theft of Automobiles. (Washington:

G.P.O, 1919), p. 1.

[7]

Johnson, “Stop Thief!” 72.

[8] "Car Insurance is Withheld from Chicago Negroes. Appaling

[sic] Auto Theft Rate Makes Negro

Districts Bigger Risks than more Refined Districts," Plaindealer (Kansas City, Kansas), July 7, 1933, pp. 1, 4.

Wednesday, February 7, 2024

Automobile Theft and the Coming of the Model T, 1908-1925

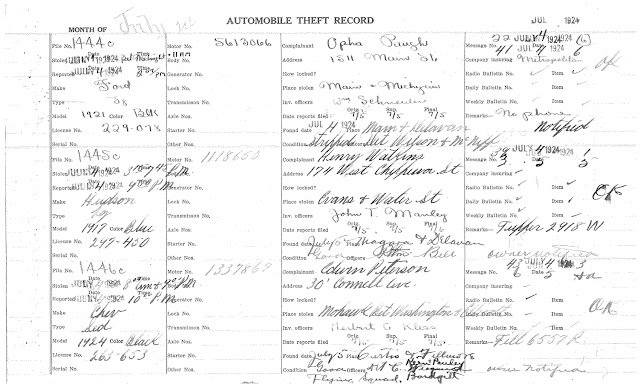

Buffalo, NY Automobile Theft Record, 1924

Mass Production and the Post-WWI Rise in Auto Theft

With Ford’s “democratization” of the automobile and an explosion in the number of vehicles came an epidemic of automobile theft. Machines produced in mass quantities made easy prey for joy riders, common thieves, and skilled, organized professional criminals. Moreover, the automobile was valuable, mobile, and its parts were often interchangeable. Lucrative domestic and international markets for stolen automobiles and parts yielded high profits and relatively low risk. Interchangeable parts also enabled thieves to quickly reconstruct and disguise stolen automobiles. As evinced by thieves’ ability to alter serial numbers, duplicate registration papers, switch radiators, and replace entire engine blocks, Fordism’s inherent uniformity welcomed theft. Moreover, thieves, with few exceptions, sought out and stole the most ubiquitous automobiles; popular, middle-priced models were most likely to be stolen, along with the easy to steal Model T.

Until the introduction of the electric self-starter in 1912, automobiles employed a battery/magneto switch along with a crank.[1] The automobilist turned the switch to B (battery), got outside the car, cranked the engine, and then once it started, moved the lever to M (magneto) and adjusted the carburetor. On early Ford Model T’s the battery/magneto switch had a brass lever key, but there were only two types, with either a round or square shank. Later, in 1919, Ford offered an optional lockable electric starter, but only used twenty-four key patterns. To make things easy for the thief, each code was stamped on both the key and the starter plate.

Most significantly, however, the very nature and scale of criminality was transformed by automobility. Unlike other stolen goods, the automobile enabled its own escape. One such real life episode happened in 1925, when five men held up a cashier and timekeeper at a construction site in the Bronx, took $2000, and then fled in the victim’s car. The New York Times reported that the thugs, “as they fled … fired a shot from the automobile at a number of workmen who had dropped their tools and were giving chase. The robbers’ car was out of sight when they reached 165th Street and Jerome Avenue."[2]

It was obvious, then, when in 1916 a New York Police official commented that: “the automobile is a very easy thing to steal and a hard thing to find.”[3] As early as 1915, 401 automobiles were stolen in New York and only 338 were recovered.[4] By 1920, it was estimated that one-tenth of cars manufactured annually were stolen.[5] Astonishingly, in 1925 it was estimated that 200,000 to 250,000 cars were stolen annually. The automobile age had ushered in a new era of crime, and a new type of criminal, the “joy rider.” [6]

This crime wave, however, could not be attributed to just one kind of criminal, particularly one who took his or her act as a casual "borrowing" of a vehicle. Automobile theft added new categories of crimes, and the motor vehicle became a central part of burglary and housebreaking. In response, police began to patrol with the automobile. In 1922, Chicago police complained that their worn-out “tin lizzies” should be scrapped; they could not catch the high powered hold-up car that traveled at sixty miles an hour.[7] Even with the growth of government and the advent of patrolling, police forces were outmaneuvered by mobile criminals. Contrary to the iconic prohibition image of police forces that smashed barrels of alcohol, municipal police forces may have dealt with stolen automobiles on a more regular basis. Automobile theft developed as a complex phenomenon, one that was not easily characterized in terms of motives or methods. Indeed it became as complex as American life in the machine age. In Philadelphia in 1926, 8,896 people were arrested for assault and battery by the automobile, as it was also used as a weapon.[8]

George C. Henderson, an expert on crime who had just authored his popular Keys to Crookdom (1924), placed car thieves into five categories: commercial thieves and hardened criminals; strippers; traveling crooks; robbers or bandits; and finally "Joy riders, kids, imbeciles, dope fiends, incorrigibles, rough-necks and members of youthful gangs [who]steal cars just to ride around town." [9] As to the "why" of youthful offenders, W.S. Jennings, commenting on those incarcerated in Indiana's Jeffersonville Reformatory, asserted that the reason for adolescents breaking the law was due to "Divorces, broken homes, children spoiled in raising by neglected parents, or by equally neglected over-indulgent ones; the absence of rational home life to counteract city temptations; failure to learn self control in early life."[10]

In reality, there were almost as many reasons for becoming an auto thief as there were thieves. One purported auto thief, writing a confession in a 1925 issue of Your Car: A Magazine of Romance, Fact and Fiction explained that he "drifted into stealing automobiles, because it seemed the easiest way to get what was to me a lot of money, quickly. I had a champagne appetite and a dishwasher income."[11] Beginning with the theft of automobile jacks, tire irons, and tires, this repentant criminal organized a gang of three, including one skilled mechanic who had "graduated from one of "Detroit's finest factories.'" The trio, careful to study the daily habits of the owners of the cars under consideration, concentrated on stealing Buicks in New York City and then moving them to a shop in Westchester. In the end, and after a chance apprehension, the writer was determined to go straight after a two year prison sentence. He cautioned owners with a strategy that remains viable to this day:

The stories I read about automobile thieves and how slick they are, opening any lock in fifteen minutes, installing wiring systems of their own and all that sort of stuff, make me laugh. Why should a thief go to all that trouble when right around the corner he can find another car without any locks on it, except the ignition lock, which his master key will open as quickly as the owners?[12]

In sum, auto theft was often one of a number of interrelated crimes perpetrated by law breakers. The automobile created new opportunities for criminals of all persuasions, and consequently confronted legal authorities with a myriad of problems. One author noted that, “as automobile thefts increase burglaries and robberies increase.”[13] The automobile itself was stolen, but the automobile also played a central role in kidnapping, rum running, larceny, burglary, traffic crimes, robberies, and deadly accidents of the “lawless years.”[14]

[1] For an excellent discussion on the history of car keys, see Michael Lamm, “Are Car Keys Obsolete,” American Heritage Invention & Technology, 23 (Summer 2008), 7.

[2] “Get $2,000 Payroll, Flee in Victim’s Car,” New York Times, September 27, 1925, 9.

[3] Roy Lewis, “Watch Your Car,” Outing, 70(May 1917), 170.

[4] Ibid., p. 168. “The All-Conquering Auto Thief and a Proposed Quietus for Him,” Literary Digest, 64(February 7, 1920), 111-115, with reference to Alexander C. Johnston’s article in Munsey’s Magazine, New York, 1920. “More Than a Quarter of a Million Cars Stolen Each Year,” Travel, (October 1929),46. See also, William G. Shepard ,"I wonder who’s driving her now?,” Colliers, 80(July 23, 1927), 14. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "joy ride" was first used in a 1909 article in the N.Y. Evening Post reporting on a city ordinance that was passed to stop city officers from taking "joy rides."

[5] For a comprehensive description of the auto theft problem in the years immediately after WWI, see Automobile Protective and Information Bureau, Annual Report (N.P.: n.p., 1921). Additionally, see the pamphlet “A Growing Crime!,” (N.P.: n.p., 1923[?].

[6] Joy rider as a term evoking irresponsibility and reckless disregard for others is briefly discussed in Peter D. Norton, “Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the invention of the Motor Age Street,” Technology and Culture, 48 (2007), 342. On juvenile delinquency in the period, see Christopher Thale, "Cops and Kids: Policing Juvenile Delinquency in Urban America, 1890-1940, Journal of Social History, 40(Summer, 2007), 1024-6; D.J.S. Morris, "American Juvenile Delinquency," Journal of American Studies, 6 (December, 1972), 337-40; Bill Bush, "The Rediscovery of Juvenile Delinquency," Journal of the Gilded and Progressive Era, 5( October, 2006), 393-402.

[7]Henry Barrett Chamberlain, “The Proposed Illinois Bureau of Criminal Records and Statistics.” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology, 13(Feb., 1922), 522. Allegedly the police moved one-third as fast as the criminals they chased.

[8]Ellen C. Potter, “Spectacular Aspects of Crime in Relation to the Crime Wave,”Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 125(May, 1926), 12. Potter noted, “…the automobile has added its spectacular element to causes for arrest in Philadelphia by approximately 10 percent. Assault and battery by the good old-fashioned human fist lacks some of the elements which make the same offense by automobile a new story and more than 8,800 arrests were made in 1925 out of a total of 137,263.”

[9] George C. Henderson, Keys to Crookdom (New York:. D. Appleton, 1924), pp. 28-9.

[10] W.S. Jennings, Jeffersonville Reformatory, City of Renewed Hope," where Indiana Keeps Some of her Misfits," Indiana Farmers' Guide, 33 (April 30, 1921), 4.

[11] "Confessions of An Auto Thief," Your Car: A Magazine of Romance, Fact and Fiction (June 1925), 34.

[12] Ibid., p. 36.

[13] William J. Davis, “Stolen Automobile Investigations.” Journal of Automobile Investigations, 28 (Jan.-Feb. 1938), 721.

[14] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Lawless Years: 1921-1933,” http://www.fbi.gvov/libref/historic/history/lawless.htm,accessed 17 May 2008.

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

Automobile Theft during the Pioneer Era, 1900-1914

The Pioneer Era

The automobile was a primary object for thieves and perfect accessory to crime during the 20th century. However, not knowing what the future held, one early turn-of-the-century contemporary asserted that the coming of the automobile would decrease personal transportation thievery substantially. An early steamer owner and physician asserted in 1901: "When I leave my machine at the door of a patient's house I am sure to find it there on my return. Not always so with the horse: he may have skipped off as the result of a flying paper or the uncouth yell of a street gamin, and the expense of broken harness, wagon, and probably worse has to be met."[1] Of course, stealing a stem car often took some time to heat the boiler, turn the various valves, and start off. Thieves would do much better with internal combustion engine powered vehicles.

The first reported auto theft in The Horseless Age occurred during the fall of 1902, although there seemed to exist some contention as to when the first took place: "H. Clark Saunders, New Brunswick, N.J. writes us that the theft of an automobile mentioned in our last issue[1903] was not the first on record, as Mr. Laurenz Schmalholz, New Brunswick, N.J., while in Trenton, N.J. on the day before the election last November [1902], had his Pierce Motorette stolen from the stables of the United States Hotel, and it was not until late the following day that the machine was found."[2]

1904 Pierce Motorette (courtesy NMAH)

The security of the steamer in particular was noted by early automotive pioneers, who clearly recognized that even their vehicles were far from secure. Of course, just the time to open valves, start the pilot flame and then heat the boiler, and do other manipulations took considerable time. For internal combustion powered vehicles, that was a different story, however. A 1901 article on locking devices for cars stated that: "It is not a safe proceeding to let an automobile stand in the street so that the operation of a conspicuous hand lever will start the vehicle; and it may be said that we are approaching a period where it will not be safe to let a vehicle stand in the street which can be started by any person thoroughly familiar with that particular machine, but without the necessary key or keys. Most manufacturers are recognizing these conditions and are providing means either against accidental starting or both against this and malicious designs."[3]

Apparently steam and electric vehicles were better equipped with locks than their internal combustion powered rivals from that era. Steam-powered vehicles typically had locks that immobilized the throttle, "thereby preventing any possible interference by the over curious meddler”.[4] For example, the Victor Steam Carriage used a particularly complex device that nevertheless did not ensure security:

…a spring actuated catch is employed, which locks the throttle lever, inside the seat, is fastened to a double-armed lever, which occupies a near horizontal position when the throttle lever is in the off position. Inside the seat there is a single-armed lever, the lower part of which stands nearly vertical normally and the upper part which is inclined forwardly. A catch on this lever engages with the one arm of the double-armed lever fastened to the throttle lever shaft and prevents the motion of the latter. The single-armed lever is held in position by a coiled spring. The upper end of the lever bears against the seatboard, and the spring is sufficiently powerful to lift the board when nobody is sitting on it. When anybody sits down when the seatboard is depressed, the spring is extended and the catch released.[5]

Typically electric vehicles came with a key that manipulated a switch, and with one turn, the current to the motor was cut off. Yet the designers of many of the earliest Internal Combustion Engine (ICE)-powered vehicles were cavalier about security. As one illustration, the Winton used a common snap switch mounted to a porcelain base. One could remove the hard rubber handle and carry it along, but it was not usually done, since the switch could be operated without it. Packards featured two push button switches that interrupted the igniter circuit. Ordinarily one of these switches was placed on the kneeboard, and the other in the battery box, which could be locked. The 1901 Hayes-Apperson used: "a switch of their own construction. The contact pieces form arcs of a circle, and over these moves a double-armed flat contact lever swiveling in the center of the circle and held down to contact pieces by a shoulder butterfly screw. This screw can easily be removed and the lever carried along."[6] But if a would-be-thief possessed a lever from one Hayes-Apperson, others could be taken. French vehicles were hardly better in terms of being designed to thwart the unauthorized driver. In a De Dion-Bouton, a slightly tapered plug was used for opening the igniter circuit when turning off the car; this plug could be carried along in the pocket of a dismounted driver. Nevertheless, any button from any De Dion-Bouton would work. But who would suspect anyone from the car-owning aristocracy of the day to possibly covet his neighbor's horseless carriage? The motives of the often suspect chauffeur, or garage owner, were different matters, however.[7]

Aftermarket manufacturers and independent inventors soon got busy developing devices to satisfy the insecurities of a growing number of automobile owners. By 1905 the Auto Lock Company of Chicago began advertising its Oldsmobile Lock, claiming that "it locks everything (even while the motor is running), prevents theft and meddling. Once used, always used."[8] In July of 1909, Orville M. Tustison of Bainbridge, Indiana, patented his "Circuit-Closer," employing a Yale-type lock with mechanical and electrical mechanisms that ultimately served as a spark coil kill switch. Located prominently on the dash board, Tustison's device was only as good as the Yale lock and box that housed the device.[9]

These and other technological devices were also limited by the effectiveness of the local law enforcement of the day. Beginning around 1910, police procedure evolved only gradually, and one might surmise haphazardly, as the car theft problem became increasingly acute. In the best-organized police departments, the report of a stolen car first resulted in an entry into the department's log book. [10] Since there was little, if any, communication among police departments in those early days, standard procedures for exchanging information did not exist, and only rarely were theft reports transmitted to other regions. Therefore, it was normally left up to insurers or vehicle owners to publish and disseminate a reward offer, and get the word out that a particular vehicle had been stolen.

It was the insurance companies who took the early lead on the matter of auto theft. During the summer of 1912 eleven insurance companies formed the Automobile Protective & Information Bureau with the purpose of disseminating material on specific stolen vehicles.[11] Depending on a number of factors, rewards ranged from $25 to $500, and notices were often printed on an 8” x 10” manila card and then mailed to nearby police departments. A woodcut, obtained from a car dealer who had used the image for advertising purposes, was stamped on the "wanted poster" along with such details as the vehicle's color, size of tires, type of headlamps, and whether the vehicle had a windshield. Given the poor roads and durability of early cars, stolen vehicles were initially rarely taken beyond the radius of 150 miles, and thus mailings were confined to the near hinterlands from where the theft had occurred. And while there was the assumption that police would do their honest best to recover the vehicle, such was not always the case.

One can only imagine, then, the consternation of automobilists when they learned that New York City police were neglecting auto theft cases.[12] Indeed, in 1914, according to the District Attorney's office, assigned detectives made no effort to pursue the criminals until insurance companies offered rewards. With that incentive, however, New York police garnered an extra $10,000 to $15,000 when they arrested twelve thieves and recovered twenty stolen cars. The reward system, also led to breaking the first auto theft ring on record. John Gargare, owner of a Lakewood, New Jersey, garage, was indicted on six counts of auto theft in 1914 by the same New York City District Attorney. Gargare and his accomplices specialized in Packards and Pierce-Arrows, demonstrating a preference for high-end vehicles that future professional auto thieves would often imitate.

The failure of local law enforcement to stem the growing tide of thefts resulted in the insurance industry taking the lead. The private sector has remained active to this day in both gathering information on the crime and tracking down the crooks and cars. At the beginning of the Automobile Age insurance policies were typically issued for only fire and damage. A 1910 article in the New York Times commented that “A great many automobilists do not give enough consideration to the theft clause of the floating fire policy. Cars are stolen quite frequently, and it is seldom that the fire insurance companies are able to trace the cars, consequently they are compelled to pay a total loss under the policy.”[13]

Losses became so great that two years later, in 1912, the National Automobile Theft Bureau (NATB) was established as an arm of the National Automobile Underwriters Conference. Supported by member insurance companies, the NATB resulted in a private police force and a nation-wide information bureau that overlapped with governmental authorities.[14] NATB personnel trained police officers and encouraged the standardization of stolen car information. And contrary to the assertions that the auto industry was neglectful of the auto theft problem, in a contentious reorganization of the NATB in 1926, it was A.C.Anderson, GM's General Comptroller, who forcefully brokered the unification of regional insurance interests into what emerged as national agency.[15]

The relationship between the NATB and local police was often tenuous, since the boundary between private and public was being crossed. With a wealth of expertise in matters related to automobile identification and the methods of criminals, NATB agents educated local police with little direct knowledge in these matters, and were active in the establishment of dedicated auto theft investigative units within police departments.[16] Yet just as the police from time to time did not escape charges of lack of motivation and corruption, insurance personnel also were subject to the temptation to personally profit from stolen cars. For example, in 1914 a chauffeur and an insurance adjuster, working together, were accused of making a small fortune in the business of hot cars.[17]

[1] The Horseless Age, (February, 6, 1901), 37.

[2] The Horseless Age, 7(May 1903), 42

[3] “Locking Devices,” The Horseless Age, (January 9, 1901), 19.

[4] The Horseless Age, (February 6, 1901), 37.

[5] Ibid, p.19

[6] Ibid, p.19

[7] On the “chauffeur problem,” see Borg, Auto Mechanics, pp. 13-30. Edwin G. Klein's The Stolen Automobile (NewYork: Lenz & Reicker, 1919) featured a thief dressed as a chauffeur in an unlikely plot that ends in the recovery of the car and a chance romance.

[8] The Horseless Age, volume 12, no. 3 xviii.

[9] U.S. Patent 928,824, July 20, 1909.

[10] National Automobile Theft Bureau, 75th Anniversary 1912-1987 (N.P.: n.p., 1987), p.6.

[11] Fred J. Sauter, The Origin of the National Automobile Theft Bureau (N.P., 1949), p.3. On the history of the NATB, see Articles of Association of the Automobile Underwriters Detective Bureau (N.P.: n.p., n.d.[1917?].

[12] "Allege that Police Work with Automobile Thieves," The Horseless Age, (April 22, 1914), 619.

[13] “Auto Insurance Growing in Favor,” New York Times, April 24, 1910, p. XX5. On the topic of auto insurance, see Robert Riegel, "Automobile Insurance Rates," Journal of Political Economy, 25 (June, 1917), 561-579; H.P Stellwagen, "Automobile Insurance," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 130 (March, 1927), 154-62.

[14] On the early history of the NATB, see National Automobile Theft Bureau: 75th Anniversary, 1912-1987 (N.P., NATB, 1987).

[15] Sauter, p.6. See Constitution and Contract Membership of the National Automobile Theft Bureau (N.P.: n.p., 1928).

[16] NATB, p.22.

[17] “Two Under Arrest Name Auto Thieves,” New York Times, January 24, 1914, p. 2.

.jpg)