From Love Affair to Troubled Marriage: 1973 and the American

Automobile Industry

For the American automobile industry, the seventies have never ended. Intense

foreign competition, high fuel prices, federal government regulation concerning

safety and the environment, quality and reliability, potential power train

transitions, and disaffected consumers all surfaced during the early 1970s and

really never went away. Yet, scholars focusing on automobile history have

utterly neglected the decade, beyond the pursuit of a few preliminary studies.

Perhaps the oversight is because these years followed the glorious 1950s

and 60s. Perhaps, it is overlooked as a consequence of the cars of the decade

often being considered by enthusiasts as being from the post-1972 "Malaise

Era." After all, you can count on your fingers the cars of the decade

worth thinking about. On a far broader scope than that of auto history,

Andreas Killen has argued that the seventies continue as "the foundling of

recent American history, claimed by no one."

Nevertheless, this period in terms of both automobile history and global

history, contains all the ingredients of revolutionary and enduring change.

Furthermore, the decade of the 1970s may be also viewed from the

perspective of American manufacturers as a time of missed opportunities. It was

an era characterized by the loss of product quality and Detroit Three market

shares due to the emergence of a rapidly changing global economy. On the

street, Americans experienced the appearance of cars equipped with ugly bumpers

and poor running engines. Additionally, a significant shift took place in the

balance of power between the federal government as a countervailing force

restraining a once unregulated industry. As one contemporary auto

industry commentator exclaimed, "Washington's hand was stretching out,

sometimes fist-like." Ultimately after years of foot-dragging and denial, Detroit

buckled to political pressures, and cars were never the same. , by the late

fall of 1973 Americans experienced Oil Shock I. Clearly, a historical

break took place that even the most detached from American society experienced.

Yet this

transition was years in the making and did not begin with the Yom Kippur War of

October, 1973 nor end with the easing of gasoline supplies in 1974. It has been

swept forward by the winds of historical continuity to this day. As it so

happened, 1973 was a point of convergence for turbulent undercurrents rooted in

the immediate past. Consequently the love affair with the American automobile

decisively turned into a troubled marriage.

To say that, however,

one must accept the notion that the love affair was not fiction; there are

scholars who make that argument. And to go one step further in defining this

essay's terrain, and to avoid confusion at this juncture, however, we must

delineate between those who loved automobility, or the flexibility that the car

provided in terms of flexible mobility, from the somewhat irrational behavior

of enthusiasts.

While many who

fell in love with the automobile in the years before 1973 live on and continue

to see the car as a freedom machine or an object of desire, those who were born

more recently, the children of this troubled marriage, often think of the car

as an appliance, second to electronic devices. After all, most of us, when we

stop and think about it, have become more dependent on PCs and I pads than on

the once cherished family automobile.

The fallout has a generational aspect, particularly among the so-called

"millennials" or Gen Y (born between 1982 and 2000). But in fact

large numbers of Americans of all ages no longer think of the motor car as an

object of desire. In fact, my recent work on the htsiory of auto theft raises

considerable doubt concerning the depth of Americans' love affair with the

automobile in the first place. After

all, why did some many car owners leave their keys in the ignition so that car

theft was so easy to accomplish, and why were Americans so casual about the

loss of their most prized possessions, as long as the vehicle was insured?

Careful

observers of contemporary American Car Culture argue that even before the

2008-9 recession something fundamental was changing as driving miles and

personal and household car ownership in the U.S. began to drop. In Detroit,

automakers are well aware of this lack of consumer interest, particularly among

this younger market segment, and have dedicated considerable resources to both

understand and remedy the problem. Most recently Brandon Schoettle and Michael

Sivak at the University of Michigan's Transportation Research Institute

published several studies on the topic of young adults (18-39) and their lack

of interest in driving. One survey released in August 2013 concluded that the

majority of unlicensed young people claimed that they were either too busy, too

poor, rode with others, or preferred to walk or bike. Less than 10% of the

group did not drive because of environmental concerns. Clearly, this group does

not have a burning desire to get behind the wheel, although about 69 percent

stated that finally within the next five years they will be getting around to

obtaining a drivers' license!

But rather than explore the troubling present, let us shift back to more solid

ground rooted in the past, namely the events of the early 1970s, and

particularly for this study, the fall of 1973. There are several

important signifiers reflective of the end of the love affair with the

automobile from that time period, including the publication of Emma

Rothschild's Paradise Lost: the Decline of the Auto-Industrial Age.

However, a discourse on Rothschild's rather shrill study would be taking a path

of least resistance. Rather, I want to explore two films that were

released in the late summer of 1973, months away from Oil Shock I, acclaimed by

critics then and now, sometimes reviewed together, and that eerily foreshadow

the impermanence of what would follow. One of these movies most all in this

room will recognize: "American Graffiti" (released August 11,

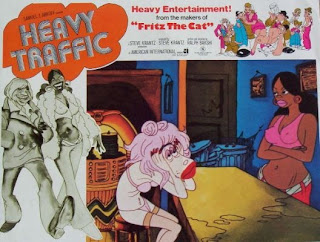

1973). The second, "Heavy Traffic," (released August 8, 1973)

is probably not familiar to many of you. New York Times film

critic Vincent Canby suggested that these two titles could be interchanged with

no loss to either. Extending Canby's remarks, I would argue that together

they anticipate the coming of a new car culture in America, and contextually

with it a new automotive industry post-1973 and indeed a new world. Cultural

representations often are imbedded with latent meanings, and that is certainly

the case of these two films, a product of their time.

I remember being sad after seeing "American Graffiti" in the theater

in 1973. For those who lived during the early 1960s, even as younger children,

it reminds us of what was perceived to be lost -- both real and imagined -- as

a consequence of the tumultuous years that immediately followed 1962. It

is a story of a loose-knit group of teenagers possessing little sense of a

larger world around them. The story is seen

through the eyes of director George Lucas, whose hometown of Modesto,

California provides the setting. It is really Lucas' autobiography of

sorts, one in which the key characters are year by year reflections of the

director's adolescent personalities as he matured between the 9th and 12th

grade. The film is also about a community of youth -- friendly, harmonious, and

with no parents around to supervise, especially on a late summer evening that

is supposedly the last for two friends who will leave for college in the east

the next morning. The 50s music creates the mood, and cars -- ever so luscious

hot rods, Kustoms, '56 T-Birds, '55 and '58 Chevys and even a two-tone Edsel --

take us rather gracefully from scene to scene. And with the exception of Curt's

(Richard Dreyfus) Citroen 2 CV, American cars are celebrated in this tribute to

the Golden Age of the automobile. And what better place to use as a stage than California,

the global epicenter of car culture then, and now."American Graffiti"

is a film about the end of one era, the Fifties, that was released just as

another was about to come to an end. The Vietnam War was essentially over, POWs

were coming home, and Morrison, Joplin and Hendrix were dead. And the love

affair with the automobile was in jeopardy, as reflected in a Seven-Up

commercial that featured a young man stepping out on his front porch while

children cry in the background. He looks longingly at his psychedelic bus on

blocks in the backyard while sipping on a Seven-Up. Clearly the Sixties were

done.

No character in the "American Graffiti" script better expressed the

love affair with the automobile than greaser and hot rodder John Milner. Not a

complex psychological figure like James Stark in Rebel without a Cause,

Milner, on several occasions however, unnervingly suggests that things related

to the automobile are about to change. At one point he remarks that "the

whole strip is shrinking" an apt inscription for the end of the 1950s.

And ironically it is Milner, of all the young people in the group, who is

most uncomfortable with change. Unlike his college bound friends, he exclaims

that he will continue to live in the valley, and "have fun, like

always." Yet, Milner's small world is a place of impermanence. His date,

Carol, represents a new generation, a fan of surfing and the Beach Boys. As

they cruise along the Beach Boys ome on the radio, and Milner exclaims, "I

don't like that surfin shit. Rock n' Roll been going downhill since Buddy Holly

died."

And while "American Graffiti" contains many light hearted scenes,

Milner's visit to a auto wrecking yard with his 14 year old date-for-the-night

Carol (Mackenzie Phillips) gets to the heart of this essay. The screen play

described it this way:

John's '32 deuce coupe crunches to a gravely

stop in front of a dark auto-wrecking yard. John and Carol get out and climb

over the fence. They walk through a valley of twisted, rusting piles of

squashed, mashed, and crushed automobiles. John sticks his hands into his

pockets moodily and looks at one of the burnt-out cars.

The wrecks are smashed

up vehicles in which young men whom he once knew died violent deaths, often

taking innocent passengers with them. He goes on to say that "All the

ding-a-lings get it sooner or later. Maybe that's why they invented cars. To

get rid of the ding-a-lings. Tough when they take someone with them." At

the time Milner placed himself in the category of the "quick." It is

only at the end of the film that we learn that John Milner would also be one of

the "the dead," the consequence of a wreck in 1964. Lucas, who along

with two others wrote the screenplay, astutely recognized that the American

love affair with the automobile was in jeopardy, but at least in 1973 had no

way of knowing just how fast or far the transition would take place. In sum,

"American Grafitti is a road film where the road led nowhere."

While it may be easy to

miss the serious side to "American Graffiti," the same cannot be said

for "Heavy Traffic." After viewing Ralph Bakshi's largely animated

release, I was disturbed. It was if the gates of hell were opened wide. Vincent

Canby summarized the film as:

American graffiti of a very high

and unusual order, a tale of a young New York City pilgrim named Michael,

half-Italian, half- Jewish, ever innocent, and his progress tough a metaphor

that is nowhere as dreary as it sounds: the pinball machine called Life. It is

a liberating, arrogant sort of movie, crude, tough, vulgar, full of insult and

wit, and an awareness of the impermanence of all things.

Like "American Graffiti, "Heavy Traffic was another

low budget film. Conflicts between

film's investors and Bakshi caused a final car chase scene to be dropped, and

one wonders what closing statement is missing. Yet what remained included a

scene featuring Chuck Berry's song "Maybelline" and Detroit "Iron"

disemboweled and disintegrated. It is a picture of automotive chaos contained

within a much larger chaotic view that is prophetic concerning what lays around

the corner in terms of American life.

Traditional moral values, relationships, standards, and material culture

was in rapid flux, to be challenged by new forms that were largely

unanticipated by even careful contemporary observers only a few years before.

While impermanence has always been a part of the American

automobile industry and American life, the rapidity of that change after 1973

coupled with associated structural transitions was unprecedented. And although

oil shocks I and II were major contributors to the dramatic rise of the

Japanese industry and the decline of the Detroit Three, they were two causal

factors, albeit important ones, among a host of other significant forces acting

synergistically at the time. The categorization and explication of those forces

are topics for a major scholarly monograph, and beyond the scope of a twenty

minute introductory talk. But certainly one reason why the automobile industry

went off the tracks was due to federal government policies that often were at

odds with one another and the average American consumer. And that is where I will start my next study,

although I plan to go much beyond that single topic.