Technological Antecedents – The Bicycle

Concurrent

to ICE technological advances were developments related to the bicycle that

took place in America

between 1880 and 1900. The bicycle created a widespread demand for flexible,

personal transportation, and it brought freedom to both women and young people.

While the nineteenth century railroads exposed Americans to rapid (for the day)

land transport, the very fact that tracks limited transverse spatial mobility

opened the door to possibilities for more adaptable movement on roadways.

Bicycles, despite their shortcomings associated with muscle power, difficult

terrain, and weather, put urban dwellers in motion. In particular, their

introduction and diffusion raised important questions concerning the quality of

roads, manufacturing techniques, social changes, and legislation. Without

exaggeration, the bicycle set the stage for the automobile that followed.

The bicycle

story began in Europe around 1819 with the

introduction of a hobbyhorse design. Its historical evolution is traced in

David Herlihy’s beautifully illustrated monograph.9 The first

mechanical bicycle is credited to the Scotsman Kirkpatrick MacMillian, who in

1839 constructed a home-built, treadle-driven device so that he could more

easily visit his sister who lived some 40 miles away. This invention was for

the most part ignored until the 1860s, when in France so-called pedal velocipedes

were manufactured by carriage maker Pierre Michaux and his son Ernest. These

designs were a cross between the modern bicycle and the wooden hobbyhorse. The

velocipede’s wheels consisted of wooden spokes and rims held together by a

steel band. The front wheel was larger than the rear, and pedals were attached

directly to the axle. With ivory handlebar grips, and a seat resembling an

animal’s spine, this awkward-looking device weighed sixty pounds. It quickly

earned itself an appropriate nickname – “the bone-shaker” – as it traversed the

rough roads of that era. In 1869 the velocipede made its way to American

shores, where a number of American firms improved its design. An American

version incorporated hollow instead of solid steel tubes, and a self-acting

brake. To stop, the rider pushed against the handlebars, thus compressing the

seat spring and causing a brake shoe to engage against the rear wheel. It was seat-of-the-pants

driving at its best, more a curiosity and sport than everyday technology.

A brief

velocipede craze followed in the late 1860s. At the same time, several social

clubs were organized. It was difficult to ride the velocipede on the bumpy roads

of the day, and one had to walk it uphill. But after 1871 interest in this

less-than-practical device waned, in part because so many of the machines built

were poorly designed. A radically new design was needed, and that would come as

a result of the efforts of Englishman James Starley, who, to this day the

British honor as the father of the bicycle industry.

In 1870

Starley introduced his Ariel bicycle. Like its predecessors, the Ariel featured

front drive pedals. However, for greater efficiency Starley made the front

wheel as large as it could be, limited only by the length of the rider’s legs,

and thus increased the wheel circumference and relative efficiency.

Correspondingly, the rear wheel was reduced in size, making it just large

enough to maintain balance. Thus, the era of the bone-shaker had ended and that

of the “high wheeler” or “ordinary” began.

English

production techniques soon incorporated steel tubes, ball bearings, and solid

rubber tires. One riding a high-wheeler could reach 20 mph, but it was

dangerous and there was always the possibility of the rider “talking a header,”

and flying over the handlebars. It was awkward and precarious, but in Britain a wide

following soon emerged as clubs of cyclists were formed.

The

American ordinary craze was fueled by the efforts of manufacturer Colonel

Albert A. Pope, a Civil War veteran from Boston

who traveled to England ,

began importing British models, took the lead in establishing the American

League of Wheel Men in 1880 and built his own models under the Columbia trademark. By 1884, Pope’s firm made

some 5,000 “Columbia” units, and the technological gap between the U.S. and the

British narrowed.10 The inherent problem with the ordinary, however,

was that its size was connected with the stature of its rider, and thus

standardization was impossible. Therefore, economies of scale in manufacturing

could not be truly achieved.

The greatest advantage of British

bicycle manufacturers during the 1880s lay in superior metallurgical

techniques. Birmingham’s W.C. Stiff (an appropriate name given the technology

he developed!) perfected a method of weld-less tube manufacture that permitted

the brazing of light tubing to solid forging. By limiting the use of heavy

gauge metal to stress points, a considerably lighter bicycle could be made

without any loss of strength. Throughout the 1880s, American manufacturers were

forced to use English tubes if they aspired to build first-class products. The

British also modified the ordinary’s design by introducing gearing in the front

of the vehicle, thus allowing the rider to pedal easier. These geared bicycles

were called Dwarfs or Kangaroos, but most bicyclists saw them as no safer than

the conventional design. If safety was an issue, and it certainly was for many

women, they moved to a tricycle. American designers also attempted to reverse

the large and small wheels of the ordinary, putting the large wheel in the back

and gearing it, thus reducing the possibility of a rider going over the

handlebars due to a sudden stop or maneuver.

Americans

made valuable technical contributions to bicycle design, particularly during

the 1880s and 1890s. Just as the Americans seemed to be taking a lead in

bicycle technology, in the mid-1880s John Kemp Starley, nephew of the creator

of the Ariel, came up with the concept of the safety bicycle. This design

featured a triangular frame, two wheels of about 2 feet in diameter, and a rear

wheel driven by a sprocket connected to a chain. While the idea was not totally

new, it was the industrial commitment to this design that was so important.

Indeed, what emerged was the notion that safety was important, so much so that

high wheelers became market curiosities by 1890.

The social

impact of the safety bicycle was enormous, particularly after 1888 when the

design was coupled with John Boyd Dunlop’s pneumatic tires. The cycling

population expanded greatly, and women, who had shunned the earlier models,

embraced the dropped frame safety bicycle design. The dropped frame was

introduced in 1888, and shortly thereafter women bicyclists’ skirts were

shortened and their ankles exposed. Women began wearing bloomers, leading

Elizabeth Cady Stanton to remark, “Many a woman is riding to the suffrage on a

bicycle.”11 Further, young men and women could now go for rides

without third party supervision. Patriarchal and matriarchal controls were

increasingly being challenged by a machine, and as machines would become more

complex with the coming of the automobile, so would the resulting social

changes.

Sales

leaped forward in the 1890s, and an acetylene flame lamp was introduced in 1895

so that cyclist could travel safely at twilight and in the dark. For several

years during the trend-driven Gay 90s, bicycling became a full-fledged boom.

Bicycle racing became a popular sport, and many colleges established bicycling

teams. Further, the bicycle inspired sheet music, trading cards, and board

games. Undoubtedly the most famous of all songs inspired by the bicycle was

Harry Dacre’s “Daisy Bell,” composed in 1892 with its chorus:

Daisy Daisy,

Give me your answer do!

I'm half crazy,

All for the love of you!

It won't be a stylish marriage,

I can't afford a carriage,

But you'll look sweet on the seat

Of a bicycle built for two!12

Give me your answer do!

I'm half crazy,

All for the love of you!

It won't be a stylish marriage,

I can't afford a carriage,

But you'll look sweet on the seat

Of a bicycle built for two!12

By 1900,

some 300 firms made more than a million bicycles in the U.S., making it a world

leader. Innovations that followed included the coaster brake, a springed fork

in the front, and cushioned tires. The cost of the bicycle halved from $100 to

$50 during the 1890s, and thus American industry liberated the bicycle from its

status as a plaything for wealthy sportsmen to a far more popular tool for

travel. In doing so, the bicycle literally paved the way for the automobile,

including the innovations of Henry Ford that would follow in the first decade

of the twentieth century.

Apart from

raising consciousness concerning flexible travel and its impact on road

improvements in the United States, no preceding technological innovation – not

even the internal combustion engine – was as important to the development of

the automobile as the bicycle. The bicycle was the object of scorn by horsemen

and teamsters long before the appearance of the horseless carriage. Further,

bicyclists gained the legislative right to use public roads in Massachusetts as

early as 1879. Key elements of automotive technology that were first employed

in the bicycle industry and then subsequently made their way into early

automobiles included steel-tube framing, ball bearings, chain drive, and

differential gearing. The bicycle industry also developed the techniques of

quantity production using specialized machine tools, sheet metal, stamping, and

electric resistance welding that would become essential elements in the volume

production of motor vehicles.

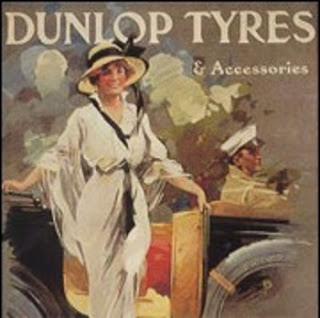

An

innovation of particular note is the pneumatic bicycle tire, invented by Dr.

John B. Dunlop in Ireland in 1888.13 Dunlop was far from working in

a vacuum, however, as numerous inventors patented similar designs during the

late 1880s and early 1890s. Also, the rubber tire had a long history that

Dunlop undoubtedly built upon. Solid rubber tires were first introduced around

1835, and in 1845 Robert William Thompson, a civil engineer from Middlesex,

England, patented a pneumatic tire similar to Dunlop’s design. An important

issue was how to keep the tire on the rim, and it was not until the early part

of the twentieth century before a system employing a wire-reinforced bead was

widely adopted. Bicycle tires were the basis of automobile tires in France by

1895 and in the United States in 1896 when the B. F. Goodrich Company

scaled up a single-tube bicycle tire for one of Alexander Winton’s early

vehicles.

The

greatest contribution of the bicycle, however, was that it provided its owner

with the ability to go when and where one wanted to. Sunday trips to

out-of-the-way scenic places were now within the reach of the common man and

his family. As one commentator of the period poignantly remarked, “Walking is

on its last legs.”14 Thus, the bike was the first freedom machine,

as it remains to this day for younger children who want to travel beyond the

pale of an observing and controlling parent. It demanded, however, muscle power

and a willingness to be exposed to the weather. To this day in many European

cities the bicycle is an environmentally-friendly alternative to the

automobile.15