This blog will expand on themes and topics first mentioned in my book, "The Automobile and American Life." I hope to comment on recent developments in the automobile industry, reviews of my readings on the history of the automobile, drafts of my new work, contributions from friends, descriptions of the museums and car shows I attend and anything else relevant. Copyright 2009-2020, by the author.

Popular Posts

-

My 1971 Porsche 911T Targa Written for younger readers: Sports car is an automobile designed more for performance than for carrying passeng...

-

Hi folks -- I was visiting with Ed Garten on Friday morning at a local Panera in Beavercreek, Ohio when Ed noticed that a Mary Kay Cadillac ...

-

So what is a rat rod? These are becoming increasingly popular, as witenssed by the several at the Friday night cruise in and today at the C...

-

Hi Folks -- Visiting back in Centerville, I read the Dayton Daily News this rainy Easter morning and found an rather lengthy article on Donk...

-

Raising an Alarm The wave of auto thefts in the early 1970s and the failure of manufacturers to make prod...

Thursday, October 31, 2019

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

The Madman Muntz

To be shown in HST 344 class on October 31, 2019!

I wish I could have known him -- an American and Southern California original!

Sunday, October 27, 2019

My 1959 MGA

The date on the back of this photograph is April, 1966. I was just about to graduate from high school and this was my first car. I paid $600 for this car and sold it later for about as much. It sat in the garage when I went to Davidson and so he could get his garage space back, my father sold it to a former high school acquaintance. It looks far better than it was -- plenty of Bondo and in need of some serious engine work, although the car never failed me while I had it. Sometimes looks are deceiving....

It had a red interior -- in fairly good shape -- and was a repaint. What problems I had were the result of my attempts to work on it. For example, when I replaced the points, I didn't think I needed all those insulating washers. Well, was I ever wrong!

The top leaked when it rained. I remember one date with Linda Janice in which her arm was soaked as she sat in the passenger seat. That ended that wished-for romance!

To this day I have a fondness for these cars, as impractical as they were. With side curtains instead of rollup windows, they were unlock able. The car would have been great in southern California, but not in upstate New York. But those nights of driving with the top down left me with a craving for convertibles that remains with me.

Fashioned by Function - Chrysler Airflow

This film will be used to supplement my text on October 29. Here is the relevant text --

Streamlining and the Chrysler “Airflop”

As articulated previously, James Flink’s argument concerning technological stagnation during the interwar years is open to revision. For example, James Newcomb has argued that in terms of shape and design, the 1930s “represent a period of the most pronounced transition in automobile styling.”15 Newcomb argues that beginning with the1931 Reo Royale and the Chrysler Airflow, rounder, smoother, and more flowing shapes were gradually introduced, and that this was due to cultural constructs that emphasized security and togetherness at the expense of individualism. In sum, it was a shift in values tied to a Depression-era culture in transition that became expressed in the way cars looked. Consequently, the automobiles of 1940 in no way resembled the automobiles of 1929, just as the America of 1940 was far different than that prior to the Great Depression.

One prominent example illustrating Newcomb’s argument is the story of the development of the Chrysler Airflow, and work in streamlining and aerodynamics in general that occurred in the automobile industry. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, there was considerable enthusiasm for aviation, and some of it spilled over into automotive areas. Indeed, the relationship between the automobile industry and aviation remains to be studied beyond superficialities. As previously mentioned, the dashboard of the Cord 810 resembled that found in aircraft of the day. Supercharging, developed at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, was installed in 1930s Mercedes and Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg models. But the rise in interest in automobile aerodynamics was also due to increases in engine size and horsepower, coupled with improved roads. The drag of a vehicle was responsible for both lower top speeds and higher fuel mileage.

One of the first individuals to explore the aerodynamics of the automobile beyond a theoretical discussion was Edmund Rumpler, who constructed his Tropfenwagen (a car the shape of a water drop) in 1921.16 The Tropfenwagen can be translated as teardrop car, or raindrop car. Rumpler’s idea was that a falling drop of liquid was nature’s perfect airfoil design. As a drop fell, it would react to the pressure around it, and in so doing, its contour minimized wind resistance or drag. Only a limited number of these vehicles were built in 1921 and 1922, and then Rumpler sold the patents to the Benz firm. A surviving example of this historical curiosity can be found in the Technical Museum in Munich.

It is unclear what, if any, influence Rumpler had on the thinking of American automobile engineers, but technical articles appearing in the 1930s suggest that Paul Jaray’s work was noticed and carefully studied in the U.S.17 The Hungarian-born Jaray was chief of the development department of the Zeppelin Airship works between 1914 and 1923. During the spring of 1921 he studied air flow passing around car bodies by using one-tenth scale wood models at the Zeppelin facility in Friedrichshafen, Germany. Jaray concluded that the vertical longitudinal section of a car was most important, and that it must be designed in such a way as to guide the air flow up and over the car in the front and down in the rear in such a manner that minimizes turbulence.

Others were thinking along similar lines during the late 1920s, and certainly one important figure was that of Carl Breer. As previously discussed, Breer, along with Owen R. Skelton and Fred Zeder, were known as the Three Musketeers at Chrysler Corporation during the 1920s. The three had formed a consulting engineering firm in 1921 after working for at time at Studebaker, and it was then that they caught the attention of Walter Chrysler. In 1924 they were instrumental in designing the Chrysler Model 70. As the story goes, Breer conceived of the Airflow concept while driving to his summer home in 1927. Traveling near Selfridge airfield, he spotted what he first thought was a flock of geese flying overhead, only to find it was a squadron of Army Air Corps planes on maneuvers. Aviation was on the minds of many Americans in 1927. In May of that year that Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic, and a new era of commercial aviation was just beginning. Breer’s insight, and his playful inquisitiveness involving the forces of air resistance to an arm extended outside his car’s window led him to ponder ideas that were being discussed much of the time, namely that of form following function. This design principle had roots in the writing and architectural work of Louis Sullivan and his far more famous pupil, Frank Lloyd Wright. The question remaining in 1927 was “Why were aircraft becoming more streamlined while cars remained little more than boxy carriages?”

Approaching the problem scientifically, Breer went to William Earnshaw, an engineer at a research laboratory in Dayton, Ohio, and provided him with a car for making measurements of air-pressure lift and distribution. He also talked with Orville Wright, who assisted Earnshaw in designing a small wind tunnel where Breer subjected various scale models consisting of blocks of different shapes to aerodynamic analysis. With the addition of smoke, airflows passing around the models could be studied in the wind tunnel. As Earnshaw discovered from these experiments, areas of lower pressure formed behind the model, and higher pressures in the front. By rounding the front of the design and tapering the rear, streamlining was achieved.18

Before long, Walter Chrysler became interested, and approved construction of a much larger wind tunnel at Highland Park, Michigan, where over the next three years researchers tested hundreds of shapes, plotted eddy curves, noted turbulence, checked wind resistance, and calculated drag numbers.19

In addition to Chrysler engineers, there were others working on streamlining at this time. Most significantly, Amos E. Northrup, who worked for the Murray Body Company, designed the 1932 Blue Streak Graham with its enclosed fenders and radiator cap under the hood. A few others had more radical solutions, especially Buckminster Fuller with his Dymaxion car.20

Fuller, one of the true design geniuses of the twentieth century, is better known for his geodesic dome structure that was first proposed in 1949. In 1928, during a period of intense study, Fuller wrote a 2,000 page essay he called 4-D, and it was from the ideas articulated in this essay that the Dymaxion car emerged. Fuller designed his streamlined automobile in an abandoned Locomobile factory located in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The first Dymaxion was produced in 1933 from plaster models, and demonstrated at the Chicago Century of Progress World’s Fair. It was a gleaming, aluminum bullet-shaped object powered by a standard Ford V-8, and was capable of going 115 mph. It brought together submarine and dirigible shapes, and there was nothing like it on the road. In this car the driver sat in the front, and there was no long hood. Shatterproof aircraft glass wrapped around the front, and sticking through the roof was a rear periscope. It was a low-slung vehicle that resembled a wingless fish and rode on just three wheels, two in the front and one in the rear. The two front wheels provided traction and braking and the rear steering. So many new ideas went into that transport: front wheel drive, air-conditioning, recessed headlights, and a rear engine. But an unfortunate accident killed the novel vehicle – even though the car was not at fault – and its major idea, streamlining, was captured by the 1934 Chrysler Airflow.

In the six years that Breer and his team spent on the Airflow project, many trial and error experiments were performed that discovered some of the practical the rules of aerodynamics. One of the conclusions suggested a modified teardrop shape that allowed for a windshield and hood.21 The Airflow was an “engineers car,” with a conventional front engine rear and drive layout, but with some important modifications. Its engine was moved some 20 inches ahead of its normal position, front end styling characterized by a short curved nose, and an integral trunk. The fuel tank and radiator were now concealed. Inside, the center latch doors were chair-height seats in a vast, spacious interior. Riders sat at almost the center of the car's balance, producing an effect described in one brochure as “Floating Ride.” Indeed, “Floating Ride” was the consequence of Breer’s insights concerning the natural rhythms of the human body and the periodic oscillations that automobiles developed because of spring height. “No matter whether you are sitting in the front seat or the back, you can relax completely and utterly . . . you can ride comfortably amidships . . . experience no bumping, bouncing or vibration of any kind. The bumps seem to flow under the car without reaching you.” Also missing from the Airflow was the typical wood and steel composite body common to virtually all other cars of the period. In its place was one complete unitized steel unit “built like a modern bridge.” Streamlining was thus achieved not only on the outside of the car, but structurally as well. Box girders ran longitudinally up from the front and were joined with vertical and horizontal members to create an exceptionally strong structure, supposedly 40 times more rigid than the conventional frame and body. With the rear seat moved 24 inches inward, and the engine now positioned immediately above the front axle, driver and passengers no long experienced the same levels of fatigue as those riding in traditionally-designed vehicles.

For all of the Airflow's virtues, many buyers just couldn't ignore its new shape. In retrospect, it was probably too different for the general public to accept. The most controversial elements were probably the rounded snout with its waterfall grill, plus slabbed sides and the spatted rear wheel openings. After its introduction in 1934 and public criticisms, modifications were made to the 1935, ‘36 and ‘37 designs, including changing the shape and size of the grill to the point where by the end of the production run, it appeared to take on a conventional appearance.22

Despite these attempts to earn public acceptance, the critics were unforgiving and unrelenting. Industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss claimed that the Airflow was a “case of going too far too fast.” Frederick Lewis Allen, editor of Harper's Magazine, described it as being “so bulbous, so obesely curved as to defy the natural preference of the eye for horizontal lines.” Because of lengthy retooling delays, the car was late coming off the line and there were rumors of it being a lemon. GM didn't help by orchestrating a smear campaign and introducing its own turret-top all steel roof automobiles in 1935. And certainly early models were plagued with flaws, as line workers had difficulty making this very new kind of car.

Chrysler responded with publicity stunts like that of Citroen where a car was dropped off a 110-foot cliff. Unharmed, the Airflow’s doors opened easily; started under its own power and was driven away. Beginning in 1935, Chrysler made outward design changes and entered the car in various endurance motor sport events. But the damage was done, and the cars would not sell. Beginning with only 12,000 units sold in 1934, the numbers continued to slide though 1937 before it was discontinued after 1938. More conventional models and a conservatively revised Airflow design called Airstream saved the company, but the whole episode is a case study in what rumors will do to undermine a technologically advanced product. From innovative leader to conservative follower, Chrysler emerged from the Airstream episode badly shaken, reluctant to take on major changes given what could happen. Throughout the 1940s, and indeed into the 1950s Chrysler was content to follow GM designs, the third of the Big Three. Chrysler’s executives were well aware that it could be trampled by the large paws of GM if it went in too bold a technological direction.

The story of aerodynamics and the automobile industry during the 1930s had a happier ending at the Ford Motor Company. It was at Ford during the late 1930s that John Tjaarda, a Dutch-born designer who had studied aerodynamics in England and served in the Dutch air force, designed the Lincoln Zephyr. The Lincoln Zephyr’s drag coefficient was lower than that of the Airflow, as was its weight. Dr. Alexander Klemin, one of the designers of the Airflow, had miscalculated and made the Airflow’s body twice as strong as it had to be.

Drag and aerodynamics were for the most part ignored in the U.S. even after World War II, the one exception being the abortive Tucker of the late 1940s. In Europe, however, car companies that included Citroen, Volkswagen, and Fiat did pay attention to aerodynamics. It was only after the 1973 fuel shock that computer-aided design and computer-aided engineering were harnessed to improve the streamlining of autos, since fuel efficiency is intimately connected with drag. Thus, it was 40 years after Carl Breer had made the bold move to study aerodynamics at Chrysler that the industry caught up.23 In the process, the engineer and the stylist were now together in terms of their functions, and thus the stylist of old, artists the likes of Harley Earl, gave way to a new type of professional in the auto industry working in the 1980s.

Saturday, October 26, 2019

Women On The Warpath (1943) - Inside The Willow Run B-24 Plant

I showed this film in my HST 344 class on October 24. It supplements my text and Powerpoint presentation.

Friday, October 25, 2019

A 1973 Porsche Targa Roadtrip to Afghanistan

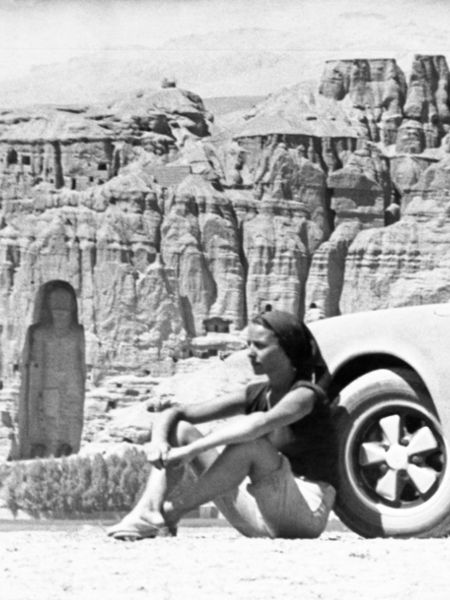

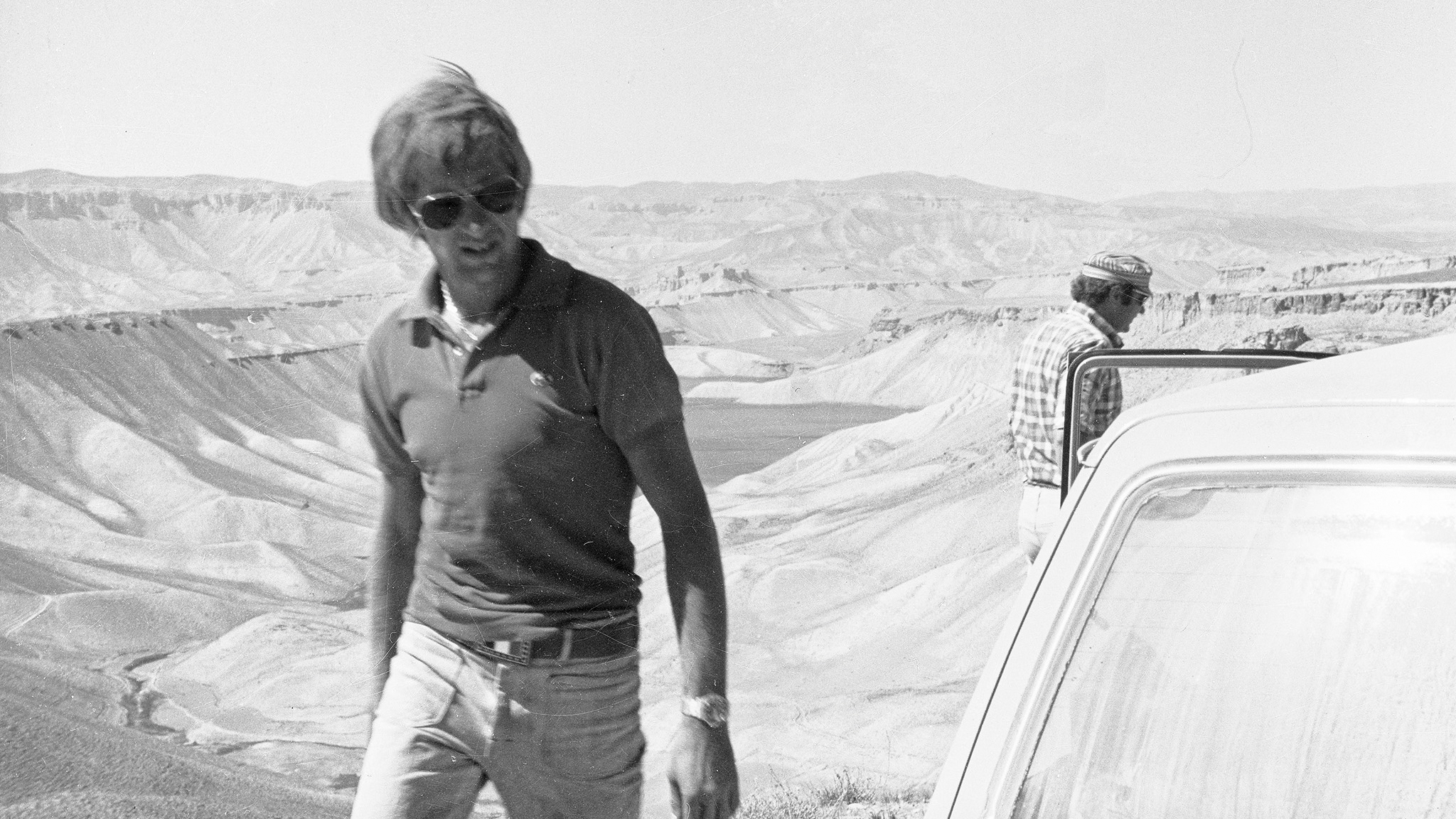

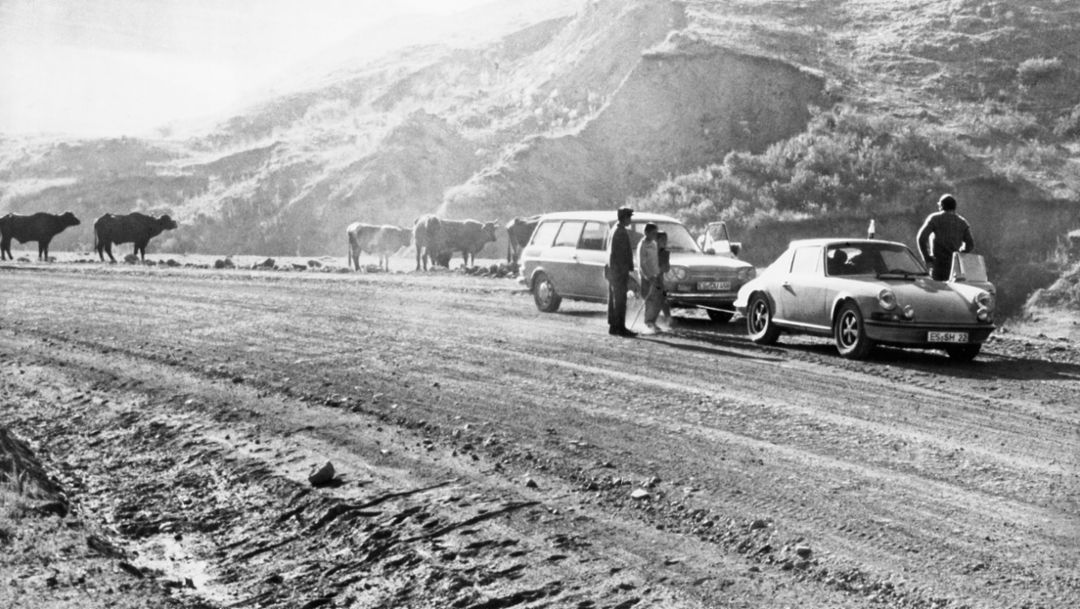

Siegfried Hammelehle is a little bit surprised. “Oh, our trip was ages ago,” he says on the phone. That’s true. Forty-six years is an eternity – especially if you consider the route of that time: three people from Germany, the United Kingdom and South Africa drove a Porsche 911 and a Volkswagen 411 from Germany over 27,000 kilometres across Turkey as well as today's Iran and Afghanistan in two months – and back again. Today it is unthinkable, but then, in August and September 1973, long before Iran became an Islamic republic and Afghanistan was an intact state – despite upheaval exactly at the time of their trip – you could dare to embark on such a journey if you had just a little courage.

That was exactly what the three did. The young British woman Carole de Gara, 23-year-old South African photographer Richard E. Lomba, known as Rick, and Siegfried Hammelehle, the 34-year-old textile entrepreneur, a great Porsche fan and owner of the car with which the trip was to be made. For 46 years the story languished in the Porsche archives – it was only published once in an old edition of "Christophorus". A coincidence brought it to light. The visual power of the few black-and-white prints and negatives and the one colour photo immediately fascinated us. And the research started. Where are these people now? The original travel notes of Rick Lomba, the trip chronicler, have unfortunately not been preserved, and he passed away long ago. Carole de Gara got married in England, but making contact proved to be difficult. This leaves the main participant and initiator: a few phone calls and e-mails later and Siegfried Hammelehle was actually located. His brother Walter established the contact and an interview soon followed.

“I was in Kabul for the first time in 1963 during a trip to Calcutta,” remembers Siegfried Hammelehle. He was there because of carpets, which he imported to Germany from all over the world. He was fascinated by Afghanistan, and wanted to travel the country in his Porsche and film it.

But who should be the cameraman? A friend of Hammelehle had an idea: Rick Lomba. The global traveller knew him from his visits to South Africa to see his uncle. Rick had been eight years old at the time, and now – in 1973 – he was studying film and theatre in England. His girlfriend at the time, Carole de Gara, was to join him as an assistant. “I just said, 'if she thinks she can do it, I don’t mind',” says Siegfried. Two films were planned: one about carpets, one about Porsche. And so the three of them left on August 5, 1973.

As for the journey itself, the three adventurers took no more than the vehicle toolkit, some spare spark plugs, oil filters and V-belts in their luggage. At some point they stopped counting the damaged tyres. But nobody got hurt. Temperatures of 50 degrees Celsius and higher in the rocky desert near Mount Ararat, and even higher temperatures in Afghanistan in the Daschte Margo – the so-called 'desert of death' with temperatures exceeding 60 degrees Celsius and absolute dryness – left deep marks in the travellers’ memories. While the Porsche ran like clockwork, the Volkswagen, which was already ageing at the time, had major problems with engine mounts, compression and electronics. However, it underwent extensive repairs in Tehran and then a talented mechanic in Erzurum in Eastern Anatolia worked on it. With a few pliers and wire, he managed to get the car going again so well that it lasted all the way home. On September 30, 1973, exactly 56 days after setting off, they reached the start point of Altbach again.

And then? The travel companions each went their own way. Siegfried's contact with Carole broke off, and with Rick it was sporadic. The film about carpets was actually broadcast by SWF, a regional broadcaster in south-western Germany, the one about Porsche sank in the Mediterranean along with the yacht of the responsible editor. Siegfried Hammelehle now lives happily with his wife and a 1970 Porsche 911 T in the Esslingen district in Germany.

Thursday, October 24, 2019

A Personal History of the General Motors Terex Division

From Ed --

John, I may or may not have told you my wife's connection to General Motors but her father was a union machinist at the Terex Division of GM (until it was sold off in the 1980s). Hudson is not far from Oberlin as you may know and both are really beautiful old "Western Reserve" towns.

Terex built the huge land movers and other heavy equipment. But Mr. Guenther was the essence of the American Dream: He grew up in a poor German family in northern Wisconsin, barely got through high school, joined the Army in WWII and because he could speak fluent "German German" was assigned as an MP transporting captured German military officers around the US to prisoner of war camps.

At the end of the war he met my late mother-in-law who had been an Army nurse. She, of course, was the daughter of the German from northeastern Ohio who had distributed Nazi propaganda around the Youngstown area and was "visited" by the FBI. The late father-in-law got a good education in a machinist school in Chicago courtesy of the GI Bill and the late mother-in-law got a master's degree in nursing from the University of Chicago also courtesy of the GI Bill.

The American Dream come true. Two poor folks entered the middle class and put three kids through college. And we inherited his machinist's tools! Such stories are ones that made America!

Mr. Guenther made a good living from General Motors but in the end he and others were told: "This is your last day. We're selling the company."

A nice little history of Terex here:

Charlie Chaplin Modern Times 1936 -- HST 344

Hi folks -- I showed the first 25 minutes this film in HST 344 on October 22. Released in 1936, the same year of the Flint GM spike that led to the formation of the UAW, it was an expression of the effects of the assembly line and speed-up on human beings. A reflection of one stream of thought, albeit from age far left, from the Great Depression, an era of widespread economic and social dislocation..

Wednesday, October 23, 2019

Call for article submissions. Society of Automotive Historians (SAH) "Automotive History Review"

Hi folks -- I just finished a new guidelines for the Automotive History Review. As the new editor, I hope to make this publication the very best specialist journal focusing on the history of automobile and related technologies, broadly interpreted. This is also a publication with a global, not American focus. I encourage you to consider sending me polished material for review and possible publication. I promise you will not be disappointed with the way your work will be reviewed.

Best wishes,

John

Best wishes,

John

Authors wishing to submit articles for publication in the Automotive History Review

are requested to follow these guidelines:

Manuscripts should not exceed 10,000 words, and should be double-spaced. An abstract is requested. Judging criteria include clear statement of purpose and testable hypothesis, accuracy and thoroughness of research, originality of the research, documentation, quality and extent of bibliographic resources, and writing style. Diagrams, graphs, or photographs may be included. Submissions are to be electronic, in Word or pdf files only, to the e-mail address below.

Possible subjects include but are not limited to historical aspects of motorized land mobility, automobile companies and their leaders, regulation of the auto industry, financial and economic aspects of the industry, the social and cultural effects of the automobile, motorsports, highway development, roadside architecture, environmental matters, and automotive marketing, design, engineering and safety.

The appropriate translation of tables, figures, and graphs can only be accomplished when sent in Word format since all files must be converted to Adobe Acrobat pdf format for publication in the Review. Remove any hidden commands (i.e., track changes) prior to submitting your electronic file. Incorporate tables in the text, rather than providing them separately.

Photographs that are not especially sharp, such as those taken in the early 20th century, should be submitted as glossies 10 ensure best-quality reproduction. More contemporary photographs may be submitted as e-mail attachments. TIFF formal is preferable 10 JPEG. Resolution should be 300 dpi, but in any case, not be less than 150.

The spelling of words that prevails in the United States should be used, e.g, "tires" rather than "tyres;" "color" rather than "colour." Dates should be expressed in the style used in the United States: month, day, year. However, if a publication is cited in which the date of publication is expressed as day, month, year, that style should be used.

Measurements should be in English; followed, if the author chooses, by the metric equivalent within a parenthesis.

Numbers over ten should be expressed in Arabic numbers (for example, "21st century." Numbers often or less should be spelled. The exception is units of quantity, such as a reference to a "4-door sedan" or a "6-cylinder" engine. If the engine is V-type, place a hyphen between the V and the number of cylinders, e.g. V-6.

Titles of articles referenced should be in quotation marks (British authors should follow the American style of double marks instead of single marks, which seems to be now common in the UK). Titles of books, journals, newspapers, and magazines should be in italics. Following American practice, the period in a sentence ending in a quote should appear following the word, not following the closing quotation mark. However, semi-colons and colons appear outside the closing quotation mark.

For ease of reference endnotes are preferable. When citing works, the following order, style, and punctuation should be used:

Rudy Kosher, “Cars and Nations: Anglo-German Perspectives on Automobility Between the World Wars,” Theory, Culture, & Society, 21 (2004): 121-144.

Alfred P. Sloan, My Years with General Motors (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday & Company, 1964), 439‑442.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I2cPBl6scJk (accessed July 17, 2008).

Where there is no doubt as to the state where the publisher is located (e.g. Boston, New York City) the state is omitted. When an endnote refers to a work referenced in the immediately preceding footnote, the word "Ibid." is used. When an endnote refers to a work referenced earlier in the article, the following style is used: Foster, op. cit., p. 54. If the author has used works that are not referenced in a endnote, they should be added at the end of the article under the title "Additional References."

Monday, October 21, 2019

Test 2 Essay Question on Tom Wolfe's "The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby"

HST 344

Dr. Heitmann

Test 2 Essay, in-class, November 12, 2019 (50 pts.)

Critics have said that Tom Wolfe’s early 1960s essays were reflective of a “New American Journalism.” In that style, reporting was written like fiction, and his work was nothing less than experimental techniques in prose bursting with observation and thoughts. The focus centered on status, culture, form and style.

You are to read three chapters from Tom Wolfe’s The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby: Chapter 2 (“Clean Fun at Riverhead”); Chapter 6 (“The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby”); and Chapter 8 (“The Last American Hero”). These segments feature demolition derby promoter Lawrence Mendelsohn, car customizers George Barris and Ed Roth, and NASCAR driver Junior Johnson. Together they provide a glimpse of the early 1960s American car culture carnival and a changing America. Discuss Wolfe’s description of that carnival, drawing on specific material from the three chapters and the main characters.

Sunday, October 13, 2019

Donald Trump at the AACA Swap Meet in Hershey, PA

OK folks, you know that this is not a political blog nor am I a terribly engaged political person. But I just got to say what follows.

The above photo was taken by Ed this week while on the swap meet fields at Hershey. There is not supposed to be political or for that matter non-auto material on the field, but it was not enforced. Indeed, the AACA national tent was within a stone's throw of where this flag was flying. There were plenty of Trump signs on the field, in carts being pulled around, and quantities to be sold or given away.

Back in October 2016 I had thought that Trump didn't have a chance to win the upcoming election, and thus was astonished to find as many signs as I did see that time around. And beautiful young girls were walking around with "I am deplorable" written on their T-shirts across their chests. Well, as we found out, Trump did better than expected, and carried Pennsylvania along with Ohio and Michigan. I should have known that day that he was more than a candidate who would be trounced in November.

So why am I writing this? Some people, like Michael Moore, are making a big deal out of the idea that Trump will will in 2020, even though poll numbers are low. Is this at all possible given what Trump does on almost a daily basis? Maybe so, but I won't help him.

In 2020 America is at the crossroads. When you vote, don't contribute the nation from taking the wrong road!

Thursday, October 3, 2019

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)