again, see previous posts for proper citation of sources. A continuance from Menno Duerksen, in Kimes, ed., Packard, A History of the Motor Car and the Company.

Initially, the Packard Proving Grounds were not independent of Detroit, but rather were an adjunct to the engineering department then headed by chief engineer Al Moorhouse (Jesse Vincent had by now moved up to vice-president in charge of engineering.) This system did not prove to work well at all, as one rather costly mistake demonstrated. Charles Vincent remembers:

“It was during the period when Packard was phasing out production of six-cylinder engines in favor of straight eights [the 626-633 models]. Due to some miscalculation either by the purchasing department or sales department, about $250,000 worth of frames for six-cylinder cars had been carried over from the year before and management was most anxious to salvage these if possible.

Beginning in 1921, the L-head engine was once again the only engine offered with a 116" wheelbase. It was officially identified as the Packard Single Six. Once the eight cylinder engine was introduced, the Six was repositioned as a mid-level luxury car competing with the Buick Master Six and later the Chrysler Six with a retail price of a 1921 5-passenger sedan listed at US$4,940 ($75,049 in 2021 dollars).

This generation introduced updated vehicle identification: 1st digit is series (Six only, Twin Sixes and Eights had their own series designation), 2nd and 3rd digits refer to wheelbase. F.e.: 233 is 2nd series Six, (longer) 133" wheelbase. 326 is 3rd series Six, (shorter) 126" wheelbase.

The line consisted of:

- 1st Series (Single Six)

- series 116, 116 in. wheelbase (1921-1922). This model was also designated the Single Six.

- series 126, 126 in. wheelbase (1922-1923). This model was also designated the Single Six.

- series 133, 133 in. wheelbase (1922-1923). This model was also designated the Single Six.

- 2nd Series (Six)

- series 226, 126 in. wheelbase

- series 233, 133 in. wheelbase

- 3rd Series (Six)

- series 326, 126 in. wheelbase

- series 333, 133 in. wheelbase

- 4th Series (Six)

- series 426, 126 in. wheelbase

- series 433, 133 in. wheelbase

- 5th Series (Six)

- series 526, 126 in. wheelbase

- series 533, 133 in. wheelbase

The Six was discontinued after the 5th series, and there was no Packard six cylinder car until the 1937 One-Ten. As the complicated naming system was revised for 1929, 626 and 633 refer to the new 1929 Packard Standard Eight in a similar way.

To accomplish this and still find room for an eight-cylinder engine, Moorhouse had designed a new and very thin water pump that required a minimum of space between the cylinder block and the radiator. Shortly after starting high speed tests, the fan belts began to fail and when I reported this, he sent out special fans that had been cut down in diameter to reduce the load on the belts. His feeling was that no customer would drive at high speed long enough to wear out the belt. With this combination, the cars completed their 25,000 miles tests with only one or two failures and the model went into production. Unfortunately, the radiators were also a bit small that year and in many sections of the country it was necessary to install larger than usual fans, this being a common remedy in those days. In every case where the larger fan was installed and, in many cases, where the regular fan was used, the water pump bearings failed in a few thousand miles. After these pumps had been redesigned a few times and. Each car campaigned [called back for repair] that many times, it was necessary to design a full-sized pump and mount it on the left side of the crankcase on a special bracket. The fan problem was then solved by counting it on a special bracket where the thin water pump had been located. All this redesigning and campaigning ran into a lot of money—about five million, as I recall.”

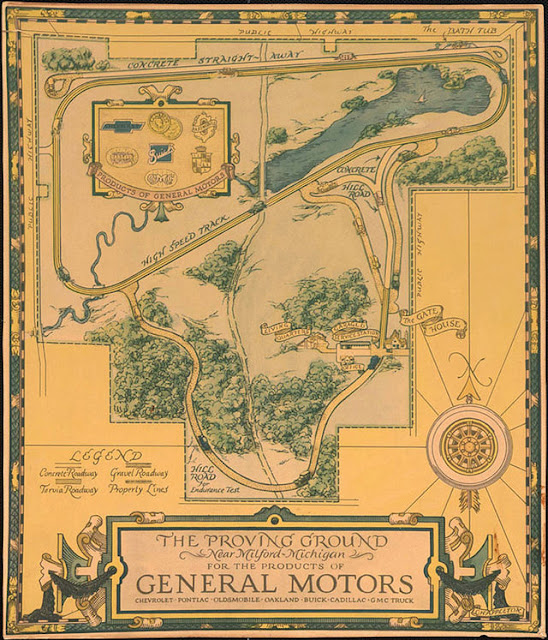

A five-million dollar loss to save a quarter of a million dollars is no way to run a business. Alvan Macauley quickly decided that the Packard Proving Grounds should be independent of, not responsible to, Engineering (as had always been the case at Milford with General Motors). And Charlie Vincent would be Lord of the Grounds.

Thereafter, any new car or new feature had to have Proving Grounds approval, in addition to an okay from Engineering and Distribution and other departments in volved in the overall scheme of production – or as Alvan Macauley admonished vice president of manufacturing E.F. Roberts in a memo, “There should be separate certificates because it is intended that each … shall pass upon the prosed improvement, particularly from the standpoint of his own department.”