Zen and the Art of Doing Automotive History Fast and Furiously

Ohio Academy of History Distinguished Historian Lecture

March 22, 2019

John Heitmann

Professor of History

University of Dayton

300 College Park

Dayton, OH 45469-1540

It has been said that the automobile is the perfect technological symbol of American culture, a tangible expression of our quest to level space, time and class, and a reflection of our restless mobility, social and otherwise. Open questions remain as to the place of the automobile in American life, and how it transformed business, and life on the farm, and vice-versa.In a complex transition between the 1890s and the present, the automobile experienced adoption, diffusion, and then became an object of social criticism. It remains a chief driving force within the American and global economies. In sum, the automobile transformed everyday life and the environment in which we operate. It influenced the foods we eat; music we listen to; risks we take; places we visit; errands we run; emotions we feel; movies we watch; stress we endure; and, the air we breathe.[1]In exploring the automobile and mobility we possess a key to understanding of the 20thand 21stcenturies.

While it has been fashionable over the last twenty years to interpret the history of technology through various social constructs and increasingly in a global or Atlantic context, it remains true that to mid-20th century individuals played a critical role in automotive history. The usual suspects for such a discussion would include Henry Ford, Billy Durant, Alfred P. Sloan, Walter Chrysler, and Harley Earl, and a mountain of historical work has appeared on these innovators.[2]For the purposes of this evening’s lecture, however, I want to focus on four other individuals with deep roots in Ohio and with a profound impact on the world-- Barney Oldfield, Charles Kettering, Richard Grant and Ned Jordan. This group is reflective of Ohio’s significance in American automotive history.[3]Even further, this story is how a handful of “Ohio players” contributed to the shaping of recent modernity in terms of speed, science-based industrial research, sales, and advertising.

*****

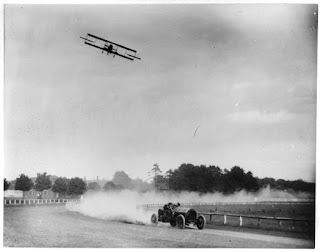

To this day, the history of automobile racing remains a neglected academic subject. Indeed, in 2014 David Lucsko asserted that one can count the number of scholarly works on the finger of one hand. He went on to say that “on balance, you are likely to encounter a greater depth of scholarship on just about any other subject in the history of the twentieth century United States.”[4] Indeed, early racing was more about speed than a utilitarian demonstration. Consequently, speed was at the center of early automotive history, and racing resulted in the widespread perception that outright speed was transformative. Racing did more than spread the word about the automobile; it was the word. In sum, as Wolfgang Sachs argued in For Love of the Automobile, competition was at the heart of the public’s dream of car ownership and their expectations for experiencing driving’s breathtaking exhilaration. [5]And while early contests were fostered by the efforts of wealthy amateurs including William Vanderbilt, it was Barney Oldfield, born in 1878 near Wauseon, Ohio, who symbolized every American male’s desire for speed. In contrast to the wealth and privilege that came with being a Vanderbilt, Oldfield was a brash and hardscrabble outsider who beat the elite at their own game[6]Oldfield lived through an impoverished childhood while working a host of manual jobs before he began racing bicycles towards the end of the 19thcentury. His big break in automobile racing came in 1902, when he agreed to pilot Henry Ford’s 999 racer, and winning a highly publicized match race against Alexander Winton. The first driver to go a mile a minute in a closed course, he doubled that speed a year later. And while he never won the most prestigious of events – the Gordon Bennett Trophy, the Vanderbilt Cup, or the Indianapolis 500, Oldfield, more than any other driver of his era, shifted the focus of auto racing from the car to the driver. His cars were memorable – the “Green Dragon,” “Blitzen Benz,” and “Golden Submarine.” But his face was so publically recognizable that he could truthfully exclaim that “You Know Me!” A mythical hero and the product of his clever and persistent media presence in film, big city newspapers, and magazines, he also had a sold-out ten week run in the Broadway musical “The Vanderbilt Cup” featuring a mock race set on treadmills between Barney and Tom Cooper.

Wearing little protective gear so that spectators could see his expression and demeanor, Oldfield became the human face to a sport where drivers were now recognized as being at the heart of competition as much or more than the cars. He could be seen chomping on a cigar as he waved to the crowd while taking the checkered flag, or coming out of the dust on the outside of the track. He excited the public imagination with thoughts of speed, exhilaration and courage. And if you are from my generation, you may remember a father’s exclamation, while being passed by a hot-rodder, blurted, “Who do you think you are, Barney Oldfield!”

*****

Speed is the consequence of power. The achievement of power by scientific and technical organization precluded satisfying the masses with production. Biographer Stewart W. Leslie has said this about Charles Franklin Kettering and his technological style: “He made corporate bureaucracy work for him. Within the largest private organization of his time he fashioned a managerial role that proved technological entrepreneurship could flourish, and one man could still make a difference.”[7]Kettering had remarkable personal qualities that distinguished him as one of the leading industrial scientists of his and any other era in American history. He was sharply inquisitive, and this trait led to an intimate knowledge associated with the problem at hand, the result of close observation and direct experience. Kettering was equally comfortable in both theory and practice, and he usually focused his attention on a commercial bottleneck where improvement seemed possible rather than striking out into completely unexplored areas. Yet he had little use for high-powered scientific theories and abstruse terminology that usually had little applicability in an industrial setting. He once said that “Thermodynamics is a big word for covering up our inability to understand temperature.”9

|

| Kettering and Knudsen, testifying on monopoly in Washington, mid-1930s |

Kettering’s major successes occurred early in his automotive career, with his electric self-starter and followed by an integrated ignition system. His self starter neither “accidental” nor “inspired.” Rather it was a deliberate, calculated attempt to bring forth a definite device. Building on the work of others before him, Kettering finally succeeded in producing his starter, and the Cadillac for 1912 came out with complete electrical equipment. Other cars soon followed. The next year, 48 manufacturers provided starters for their machines, and in 1914 there remained only five companies, or about 8% of all companies, that did not offer this feature. Thus, what would have been regarded as a luxury before 1912 became a necessity by 1914. A little later, electric starting was offered even on the Ford. And with that device women in increasing numbers got behind the wheel, profoundly altering American society.

He subsequently sold this ignition coil design to Henry Leland at Cadillac, and this success would not only form the basis of the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company (Delco) but also further work leading to an integrated electrical system. That technology involved a self starter, generator, voltage regulator and lighting units, which were also first sold to Cadillac before being marketed to other companies.11By early 1913, Delco occupied three floors of a rented factory building in East Dayton, Ohio, employed 1,500 workers, and had sold a total of 35,000 starting, lighting, and ignition systems. Despite the catastrophic Dayton Flood of 1913, Delco continued to grow, and thus by the end of that year the firm tripled its annual output, to more than 45,000 units. Profitable and innovative, it would be purchased by Billy Durant at General Motors in 1916.

Kettering’s successes at General Motors as head of research would far outweigh his failures. Yet he once said, “You must learn how to fail intelligently, for failing is one of the greatest arts in the world.” After a discouraging failure in 1924 involving the development of an air-cooled mass-produced vehicle, success came to Kettering when a General Motors reorganization rationalized research with manufacturing, marketing, and design.

All that was left to be done, in the words of Kettering, was to “keep the customer dissatisfied.”[8]It was a different kind of challenge, one demanding a series of enhancements rather than revolutionary change. Technological changes related to automotive lighting, paint, suspension, the engine, and drive train were made incrementally during the 1930s. To achieve those innovations a new 11-story brick building was opened in Detroit, where by the late 1930s a staff of 400, including 100 degreed scientists and engineers worked in an interdisciplinary fashion.

But the looks of the vehicle became increasingly critical to the annual model change, in advertising copy, and consequently in attracting consumers. It was a strategy of planned obsolescence. The result was technological stagnation. After the introduction of strip steel in 1932 and the adoption of the all-steel body, the industry experienced no further watershed innovations. The post-WWII era saw a new Kettering overhead valve V-8 engine introduced with the Oldsmobile Rocket 88 in 1949, afterwards European manufacturers and suppliers became the innovators, of everything from front wheel drive cars, torsion bar suspension, disc brakes, and fuel injection.

Without Kettering, Dayton would not have become the city that it was prior to the 1970s, nor would GM. Next to Flint, Michigan, and perhaps Russelheim, Germany, no city had been influenced by GM’s success more than Dayton, Ohio.[9]With a history in agricultural implement manufacture and the birthplace of the National Cash Register Company, Dayton was home to a large number of skilled machinists who subsequently found employment in the rapidly-growing automobile-related firms established by Boss Kettering and his associates. According to Fortune,in 1938 approximately 100,000 of the 200,000 residents of Dayton owed their economic livelihoods directly to General Motors. Not all of these activities were strictly involved automobile manufacturing. Frigidaire employed 12,000 workers making refrigerators, beer coolers, air conditioners, electric ranges, and water heaters. Nearby, in central Dayton, Delco Products made electric motors not only for Frigidaires, but also for Maytag washers, Globe meat slicers, and DuPont rayon spinners. It was estimated that some 10 million motors worldwide could be traced back to Dayton. Additionally, Delco made coil springs and shock absorbers for GM, Nash, Hudson, Graham, and Packard automobiles. Finally, Delco had a brake operation, making hydraulic brake assemblies and brake fluid while housed in perhaps the only flop to bear GM’s corporate name, General Motors Radio. Often overlooked, GM’s Inland Manufacturing in Dayton had its origins in WWI and the Dayton-Wright Airplane Co. After the war, its woodworking department formed the basis of an enterprise to make wooden steering wheels and later rubber-based ones. Product diversification followed, so that the firm made everything from rubber cement to running boards, motor mounts, and weather strips. To borrow a phrase from a book boosting the city during the 1950s, truly GM’s Dayton operations were at the heart of was “dynamic Dayton.”

*****

Brought more to GM than just technical expertise. Kettering brought talent that made crucial contributions to GM’s efforts to surpass the Ford Motor Company during the Interwar years. One of his closest associates at Delco was Richard H. Grant, who drew on his experiences at National Cash Register and the sales philosophy of John Patterson to teach GM to sell – first Chevrolets and then the entire product line. Known as “Dynamic Dick” as well as the “Little Giant,” Grant was one of America’s great salesmen. Born in Massachusetts and educated at Harvard, Grant learned to sell at NCR, became its general sales manager in 1913, later moved to Delco and Frigidaire, and in 1923 joined Chevrolet as sales manager. In 1929, Grant became a GM vice-president and was one of the top four or five executives of the firm during the 1930s, with memberships on six policy groups.

The “Little Giant” played a major role in reorganizing the distribution system at GM, eliminating distributors who previously held large territories and had control over local dealers. He was an orator and showman, but beneath the surface Grant was a careful, systematic thinker who implemented market research, accounting, and training procedures throughout the corporation. Grant had learned seven fundamentals of sales from NCR’s John Patterson that were subsequently instilled into GM personnel:

1. Have the right product.

2. Know the potential of each market area.

3. Constantly educate your salesmen on the product, making them listen to canned demonstrations and learn sales talks by heart.

4. Constantly stimulate your sales force, and foster competition. among them with contests and comparisons.

5. Cherish simplicity in all presentations.

6. Use all kinds of advertising.

7. Constantly check up on your salesmen, but be reasonable with them and make no promises you can’t keep.15

Grant further refined Alfred Sloan’s notion of using R. L. Polk Company’s monthly state registration data to closely monitor subtle shifts in consumer demand. By the late 1920s, this information would be relayed to William Knudsen’s production group, thus ensuring that the automobiles made would be the kind that customers would quickly buy off dealer’s lots. After the Depression hit, Grant responded in 1932 with an aggressive strategy of reorganization and renewed energy centered on the formation of the Buick-Olds-Pontiac Sales Company. Grant’s legacy included: the use of roadside billboards and radio for advertising Chevrolets; the mailing of postcards informing owners of new models; and at the tail end of his career the first sponsored TV show (“The Dinah Shore Show”).

*****

The Jordan automobile presents a different story but with a similar ending. The Jordon was the result of the vision and energy of Edward S. “Ned” Jordan.[10]Born in 1881 and educated at the University of Wisconsin, Jordan’s career included a stint in advertising at the National Cash Register Company in Dayton and in a similar position with the Jeffery Automobile Company, located in Kenosha, Wisconsin. In 1916, Jordan organized his own automobile company in Cleveland, Ohio, with the idea that the firm’s vehicles would manufacture cars that cost not quite as much as a Cadillac but more than a Buick. Always relatively expensive and assembled from parts, engines, and bodies made elsewhere, about 80,000 units were sold between 1916 and 1931. At $2,000 plus, the Jordan was marketed at the well-to-do.

The Jordon was noteworthy for several reasons. Ned Jordan had an uncanny understanding of fashionable American consumers from the point of view of color. His cars could be ordered in a number of unusual shades, long before the color revolution of the mid-to-late 1920s. As early as 1917 Jordan cars could be purchased in colors such as Liberty Blue, Pershing Gray, Italian Tan, Jordan Maroon, Mercedes Red, and Venetian Green. And when the “True Blue” Oakland was introduced in 1923, Jordan quickly followed with its 1923 Blue Boy model. Secondly, Jordan understood the post-WWI youth market and responded with the marque’s most famous model, the Playboy. Supposedly, the Playboy idea was the result of Ned’s dance with a 19-year old Philadelphia socialite, who quipped, “Mr. Jordan, why don’t you build a car for the girl who loves to swim, paddle and shoot and for the boy who loves the roar of a cut out?”[11]Ned would later refer to this as a million dollar idea, and the Playboy was born. Jordan had a gift for writing advertising copy; in 1920 a Jordan Playboy ad suggested a visit to a local bordello:

Somewhere far beyond the place where man and motors race through canyons of the town – there lies the Port of Missing Men.

It may be in the valley of our dreams of youth, or the heights of future happy days.

Go there in November when logs are blazing in the grate. Go there in a Jordan Playboy if you love the spirit of youth.

Escape the drab of dull winter’s coming – leave the roar of city streets and spend an hour in Eldorado.[12]

As a flamboyant advertising copywriter, Jordan’s Playboy ad copy written in 1923, “Somewhere West of Laramie,” transformed American automobile advertising. [13]The early days of automobile advertising often emphasized specific features of an automobile. This style of advertising was swept aside by Jordan in the mid-1920s.[14]

While traveling on a train across the flat and monotonous Wyoming plains, a tall, tan, and athletic horsewoman suddenly appeared, racing her horse toward Jordan’s window. For a brief moment the two were rather close as the woman smiled at him; then she turned and was gone. Jordan asked a fellow traveler where they were: “Oh, somewhere west of Laramie,” was the desultory reply. Within minutes he composed an immortal ad that later appeared in the Saturday Evening Post. Beneath an illustration of a cowgirl racing a sporty Jordan roadster against a cowboy straining to push his fleet-looking steed to catch up with her, there appeared these words:

Somewhere west of Laramie there’s a bronco-busting, steer roping girl who knows what I am talking about. She can tell what a sassy pony, that’s a cross between greased lightning and the place where it hits, can do with eleven hundred pounds of steel and action when he’s going high, wide and handsome.

The truth is the Playboy was built for her.

Built for the lass whose face is brown with the sun when the day is done of revel and romp and race.

Step into the Playboy when the hour grows dull with things gone dead and stale.

Then start for the land of real living with the spirit of the lass who rides, lean and rangy, into the red horizon of a Wyoming twilight.

The Playboy sold like hot cakes, and this ad galvanized the auto industry. Soon Chevrolet and Rickenbacker responded with ad lines “All outdoors can be yours,” and “The American Beauty,” respectively.[15]Previously ads mentioned the features of the car, but with the Jordan ad new parameters came into play – freedom, speed, and romance. Emblematic was the fact that the practical Model T's life had come to an end. Now art and color would be the keys to auto sales. Advertising was ultimately directed to influencing the human spirit, as modernity now worshiped things with promises.

*****

In closing, I have told the story of four Ohioans whose contributions within the American Automobile industry were transcendent beyond it. Modernism means many things to scholars, but it seems rather obvious that speed, scientific and technical industrial research, the art of selling and advertising had a profound impact on modern life and what it means to be human. With the closing of the Lordstown, Ohio, assembly complex, the demands of economies of scale, the shift in markets, and labor dislocations are again front-page news. Yet the stories of Barney Oldfield, Boss Kettering, Richard Grant, and Ned Jordan are timeless and encouraging. Their stories demonstrate the possibilities attached to personalities and new ideas.

[1]A number of recent essays and books have taught me to think differently about the history of the automobile. They include Gijs Mom, Atlantic Automobilism: Emergence and Persistence of the Car, 1895-1940(New York, 2015); Cotten Seiler, Republic of Drivers: A Cultural of History of Automobility in America(Chicago, 2008); Sally H. Clarke, Trust and Power: Consumers, the Modern Corporation, and the Making of the United States Automobile Market (Cambridge, UK, 2007); Bernhard Rieger, “Fast Couples’: Technology, Gender, and Modernity in Britain and Germany During the Nineteen-Thirties,”Historical Research, 76 (August 2003): 364-88; Rudy Kosher, “Cars and Nations: Anglo-German Perspectives on Automobility Between the World Wars,” Theory, Culture, & Society, 21 (2004): 121-144; Wolfgang Sachs, For Love of the Automobile: Looking Back into the History of Our Desires(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992); Sean O’Connell, The Car and British Society: Class, Gender and Motoring 1896-1939(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998).

[2]Definitive histories on Ford include Allan Nevins,Ford, 3 vols., (New York: Scribner, 1954-1963); Robert Lacey, Ford, the Men and the Machine(New York: Little, Brown, 1986); John Bell Rae, Henry Ford(New York,: Prentice-Hall, 1969); Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress, 1903-2003(New York: Viking, 2003); Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century(New York: Knopf, 2005); Anne Jardim, The First Henry Ford: A Study in Personality and Leadership(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970). On his early years, see Sidney Olson, Young Henry Ford: A Picture History of the First Forty Years (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1963). On Durant, see Axel Madsen, The Deal Maker: How William C. Durant Made General Motors(New York: Wiley, 1999); Lawrence R. Gustin, Billy Durant: Creator of General Motors(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973). On Sloan, see David R. Farber, Sloan Rules: Alfred P. Sloan and the Triumph of General Motors(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). Among Sloan’s writings are Adventures of a White Collar-Man(New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1941); My Years with General Motors(Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964). For a contemporary look at Sloan, see “Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., Chairman,” Fortune17 (April 1938): 72-7. See also Stephen Bayley,Harley Earl and the Dream Machine (New York: Knopf, 1983); Harley Earl(New York: Taplinger, 1990); Anthony J. Yanik, “Harley Earl and the Birth of Modern Automotive Styling,” Chronicle: TheQuarterly Magazine of the Historical Society of Michigan, 21(1985), 18-22; Sally Clarke, “Managing Design: the Art and Colour Section at General Motors, 1927-1941,” Journal of Design History12 (1999): 65-79.

[3]On the history of the automobile industry in Ohio, see Robert R. Ebert, “From Garfords to Fords,” Automotive History Review, 53(Autumn, 2011), 4-18;Richard Wagner, Golden Wheels: the Story of Automobiles Made in Cleveland and Northeastern Ohio 1892-1932(Cleveland, 1986). Steve Meyer, “An Economic Frankenstein”’: UAW Workers’ Response to Automation at the Ford Brook Park Plant in the 1950s,” Michigan Historical Review, 28 (March, 2002), 63-89; David A. Hounshell, “Ford Automates: Technology and Organization in Theory and Practice,” Business and Economic History, 24 (1995), 59-71; Gregory D.L. Morris, “When Cleveland as Motown,” Financial History, 114 (Summer, 2015), 32-5; Frank E. Wrenick, Automobile Manufacturers of Cleveland and Ohio, 1864-1942. (Jefferson, NC, 2016).

[4]David N. Lucsko, “American Motorsports: The Checkered Literature on the Checkered Flag,” The most important question related to the history of auto racing is often raised but remains to be carefully and systematically answered. Namely, what is the influence, and vice-versa, of racing on the technical development of production vehicles? This rationale was used frequently in justifying the horrific death toll that took place on tracks and circuits to the 1970s. What has been far better demonstrated are the connections between advertising and racing, and utility and reliability trials, starting with John Rae Bell’s The American Automobile (1965). Of the work I would consider “academic,” one of the best was written by a non-academic, Griffith Borgeson, The Golden Age of the American Racing Car(New York, 1966). See also W. David Lewis, Eddie Rickenbacker: An American Hero in he Twentieth Century(Baltimore, 2005); Robert C. Post, High performance: The Culture and Technology of Drag Racing (Baltimore, 1994); Ben A. Shakelford, “Masculinity, the Auto Racing Fraternity, and the Technological Sublime: The Pit Stop as a Celebration of Social Roles,” in Roger Horowitz (ed.), Boys and their Toys? Masculinity, Class, and Technology in America(New York, 2001).

[5]Sachs,For the Love of the Automobile; Tom McCarthy, Auto Mania: Cars, Consumers, and the Environment(New Haven, 2007); Brian Ladd, Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automobile Age (Chicago, 2008).

[6]Timothy Messer-Kruse, “You Know Me: Barney Oldfield,” Timeline, 19, no. 3 (2002): 2‑19; William F. Nolan, Oldfield; the Life and Times of America’s Legendary Speed King(New York, 1961); Mark D. Howell, ‘“You Know Me!’ Barney Oldfield and the Creation of a Legend,” Automotive History Review, 36 (Summer, 2000), 26-30.

[7]Stewart W. Leslie, Boss Kettering(New York: Columbia University Press, 1983). In addition to Leslie’s fine biography, see Sigmund A. Lavine, Kettering: Master Inventor(New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1960); Rosamond McPherson Young, Boss Ket: A Life of Charles F. Kettering(New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1961). “General Motors: Boss Ket, Vice President and Distinguished Head of the Research Laboratories Division,” Fortune19 (March 1939): 44-52.

[8]Leslie, pp.182-205.

[9]“General Motors,” Fortune18 (December 1938): 40-7, 146.

[10]On the Jordan Motor Car Company, see James H. Lackey, The Jordan Automobile: A History(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005).

[11]Lackey, 24.

[12]Literary Digest(November 13, 1920): 94-5.

[13]My understanding of advertising and history was shaped by the following sources: Pamela Walker Laird, “ ‘The Car Without a Single Weakness’: Early Automobile Advertising,” Technology and Culture(1996): 796-812; Peter Roberts,Any Color So Long as its’ Black . . . the First Fifty Years of Automobile Advertising(New York, 1976); Yasutoshi Ikuta, American Automobile: Advertising from the Antique and Classic Eras(San Francisco, 1988); Helen Damon-Moore, Magazines for the Millions: Gender and Commerce in the Ladies Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post(Albany, 1994); T.J. Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York, 1994); William M. O’Barr, Culture and the Ad: Exploring Otherness in the World of Advertising(Boulder, CO, 1994); Daniel Pope, The Making of Modern Advertising(New York, 1984); Judith Williamson, Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising (London, 1978); Claude Hopkins, My Life in Advertising(New York, 1927); Richard Tedlow, New and Improved: The Story of Mass Marketing in America(New York, 1990), Chapter 3; Julian L. Watkins, The 100 Greatest Advertisements: Who Wrote Them and What They Did(New York, 1959).

[14]On the Jordan Motor Car Company, see James H. Lackey, The Jordan Automobile: A History(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005).

[15]“Automobiles II: The Dealer,” Fortune(December 1931): 43.

Thanks for share this articles

ReplyDeleteeva air vn

ReplyDeletevé máy bay đi california

số điện thoại hãng korean air

vé máy bay từ sài gòn đi mỹ

đặt vé máy bay đi canada

Cuoc Doi La Nhung Chuyen Di

Du Lich Tu Tuc

Tri Thức Du Lịch