Gone in Sixty Seconds: Joyriders and Criminals

With Ford’s

“democratization” of the automobile and an explosion in the number of vehicles

came an epidemic of automobile theft. Machines produced in mass quantities made

easy prey for “joy-riders” and professional criminals. Moreover, the automobile

was valuable, mobile, and its parts were interchangeable. Lucrative domestic

and international markets for stolen automobiles and stolen parts yielded high

profits. Interchangeable parts also gave thieves the opportunity to quickly

reconstruct and disguise stolen automobiles. As evinced by thieves’ ability to

alter serial numbers, duplicate registration papers, switch radiators, and

replace entire engine blocks, a nascent uniformity welcomed theft. Moreover,

thieves sought out and stole the most ubiquitous automobile; popular,

mid-priced models were most likely to be stolen, along with the easy to steal

Model T. As early as 1910 joyriding and automobile theft were problems for the

automobilist. Major concerns centered on the unauthorized use of an owner’s

vehicle by a chauffeur or a parking attendant. To that end a number of devices

were marketed, from a gear shift lever lock to recorders that kept tabs on when

a vehicle was actually being driven.84

Until the

introduction of the electric self-starter in 1912, automobiles employed a

battery/magneto switch along with a crank.85 The automobilist turned

the switch to B (battery), got outside the car, cranked the engine, and then

once it started, moved the lever to M (magneto) and adjusted the carburetor. On

early Ford Model T’s, the battery/magneto switch had a brass lever key, but

there were only two types, with either a round or square shank. Later, in 1919,

Ford offered an optional lockable electric starter, but only used twenty-four

key patterns. To make things easy for the thief, each pattern was stamped with

a code on both the key and the starter plate. Would-be joy-riders needed only a

little luck to drive off with any unguarded Model T.

Unlike

other stolen goods, the automobile enabled its own escape. As one author

observed in 1919:

Not

only is the motor vehicle a particularly valuable piece of

property . . . but it furnishes at the same time an almost ideal

getaway . . . With the automobile there is no planning to

be done. With a thousand divergent roads open to him and a vehicle possessing

almost unlimited speed, escape is practically automatic.86

A New York

Police official commented in 1916 that, “the automobile is a very easy thing to

steal and a hard thing to find.”87 As early as 1915, 401 automobiles

were stolen in New York and only 338 were recovered.88 By 1920, it

was estimated that one-tenth of cars manufactured annually were eventually

stolen. Astonishingly, perhaps, in 1925 it was estimated that 200,000 to

250,000 cars were stolen annually.89 Table 2 provides theft data for

major American cities.

Table 2. Automobile Thefts in Major American Cities,

1922-1925

|

City |

Year |

|||

|

1922 |

1923 |

1924 |

1925 |

|

|

New York |

7,107 |

7,959 |

10,064 |

11,895 |

|

Chicago |

3,636 |

2,334 |

4,946 |

7,587 |

|

Detroit |

3,194 |

4,428 |

7,187 |

11,750 |

|

Los Angeles |

4,802 |

4,218 |

7,326 |

8,392 |

|

San Francisco |

1,960 |

2,154 |

3,257 |

3,746 |

|

Dayton |

249 |

313 |

366 |

485 |

Source: Automotive Industries, 56 (February

19, 1927), 283.

Further,

the automobile created new opportunities for criminals and confronted legal

authorities with a myriad of problems. One author noted that, “as automobile

thefts increase burglaries and robberies increase.”90 The automobile

itself was stolen, but the automobile also played a central role in kidnapping,

rum running, larceny, burglary, traffic crimes, robberies, and the deadly

accidents of the “lawless years.”91 The Baltimore Criminal Justice

Commission reported that

In August, 1922, one of Baltimore’s

well known and highly respected citizens was held up, robbed of $7000 and

brutally murdered in broad daylight on the busy thoroughfares of the city. The

bandits perpetrating this carefully planned crime escaped in a high powered car

bearing stolen license plates.92

In 1924,

Arch Mandel of the Dayton Research Association observed, “The motor vehicle has

ushered in a new era of crime and police problems, and apparently a new type of

offender.”93 “To cope with this problem” Mandel wrote, “police

departments have been obliged to detail special squads and to establish special

bureaus for recovering stolen automobiles . . . this has

added to the cost of operating police departments.”94 Consequently,

the increase in mobility was matched with a growth in government. The cost of

police work in cities with populations over 30,000 rose steadily from

approximately $38 million in 1903 to $184.5 million in 1927.95

Automobile theft added new categories of crimes, and as a piece of technology

became a central part of burglary and housebreaking. In Philadelphia, 8,896

people were arrested for assault and battery by the automobile.96 In

response, police began to patrol with the automobile. In 1922, Chicago police

complained that their worn-out “tin lizzies” should be scrapped; they could not

catch the high powered hold-up car that traveled at sixty miles an hour.97

Even with the growth of government and the advent of patrolling, police forces

were out-maneuvered by mobile criminals. Contrary to the iconic Prohibition

image of police forces smashing barrels of alcohol, municipal police forces may

have dealt with automobiles on a more regular basis.

Automobile

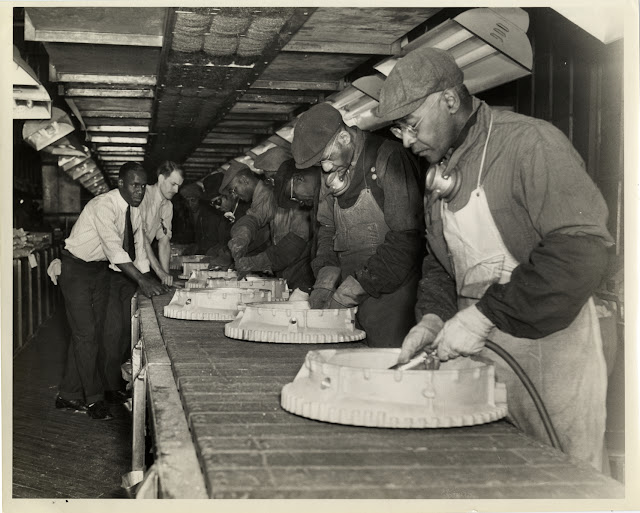

theft was most acute in Detroit and Los Angeles. “Naturally Detroit is

peculiarly liable to this trouble because it has such a large floating

population of men trained in mechanical expertise in the various factories.”98

It stood to reason that Ford’s workers stole Ford’s Cars. In Detroit, in 1928,

a total of 11,259 cars were stolen.99 The same year in Los Angeles

10,813 automobiles were stolen.100 By the 1920s, Los Angeles had the

most automobiles per resident in the United States. Historian Scott Bottles

pointed out, “By 1925, every other Angelino owned an automobile as opposed to

the rest of the country where there was only one car for every six people.”101

Angelinos had more opportunities to steal cars. Baltimore, New York City,

Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, Omaha, St. Louis, and many other cities also

experienced major problems related to automobile theft. In an article published

in Country Life, Alexander Johnson

revealed the problem was not just endemic to urban America: “We who live in the country are not quite as

subject as our urban brethren to this abominable outrage, but automobile stealing

is carried on even in the rural districts.”102

The cost of

police work in state governments also rose from approximately $98 million in

1915 to $117 million in 1927.103 To combat auto theft, state

governments created license, registration, title, and statistical bureaus and

urged the federal government to become involved. E. Austin Baughman,

Commissioner of Motor Vehicles of Maryland, cited 1919 as “the climax of an epidemic

of car stealing” with 922 cars stolen, 709 recovered, and 213 missing.104

Baughman urged the country to adopt a Title Law which would assure all motor

vehicles could be identified and located through the name and address of the

owner on record. 105 The bureau helped Maryland to gather

statistics:

. . . one can in a

comparatively short time find anything from how many 1912 Cadillacs are still

in existence in this state, to how many more Fords were stolen than Chevrolets

in 1923 or 1922; and from how many six- and seven-ton trucks are still in use

in Maryland and to what percentage of cars stolen in 1923 are still missing.106

In 1920, Massachusetts developed a similar program under the

used-car department of the Department of Public Works.107 States that

did not pass title laws were a nationwide liability and became alleged “dumping

grounds” by neighboring states.108

The

inter-state nature of automobile theft demanded federal intervention. The

automobile nullified state boundaries and contributed to the nationalization of

crime fighting. Arch Mandel wrote in 1924 that, “State lines have been

eliminated by the automobile” and the “detection of criminals is becoming more

and more a nation-wide task.”109

In 1919,

Congress passed the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, which received the

appellation of its sponsor, Senator Leonidus Dyer. The Dyer Act promulgated

that thieves receive fines of $5,000 and 10 years in prison, or both. The

American Automobile Association lobbied congress to pass the Dyer Act.110

Consequently, between 1922-1933 auto thefts were the most prominent federal

prosecution of interstate commerce.111

During the

first two decades of the twentieth century, of auto theft was blamed on the

owner negligence. A 1916 insurance company pamphlet entitled “Emergency

Instructions,” warned owners that “when dining in a public restaurant the

driver of the car should be seated in such a position that he can observe his

car.”112 Basic instructions also warned to “not leave your car

unprotected on the street or any place at any time.”113 However, in

1922 many automobile owners left keys in their unlocked cars.114 An

article in Popular Mechanics Magazine observed,

“Approximately seventy-five percent of all the cars that were not stolen were

not locked at all.”115 One author chastised drivers for leaving

automobiles unattended for an hour or more.116 Beyond common-sense

precautions, automobile owners were advised to take preventive measures to stop

early car thieves. Owners were advised to lock their doors or “garage” their

automobiles. In his 1917 article “Automobile Thefts,” John Brennan proposed one

countermeasure: “If owners would only

take steps to put private identification marks on their cars, the problem of

automobile thievery would be a simple one to solve.”117 It was

suggested that the owner bore holes into the underside of the running boards,

scratch their name somewhere secret, or tape an identification card inside the

upholstery.118 A 1926 article in Popular

Mechanics passed on to readers one motorist’s intricate plan of fake coils

and pseudo ignition connections.119 Other articles proposed that

owners disconnect the magneto. In any case, the prevailing attitude of the day

was that automobile theft was usually the owner’s fault. In 1929, E. L.

Rickards, manager of the Automobile Protective and Information Bureau in

Chicago, stated: “A man or woman who leaves his car unlocked and unattended is

committing an offense against society.”120

Thieves

were recognized as frauds, joy-riders, professionals, and gangs. They stole a

range of models, but mostly low-priced Chevrolets, Plymouths, Chryslers, and

Fords.121 Furthermore, automobiles were most likely to be stolen in

business or entertainment districts, where individuals parked the same models

in the same place. Often a thief caught red-handed simply claimed that they had

hopped into the wrong car. When interrogated by a judge, one thief explained

why he was in the wrong Ford: “Because both cars are Fords, and all Fords look

alike, not only to me but to their owners.”122 Charges were dropped.

Despite preferences to steal commonplace vehicles, elite and unusual

automobiles were not exempt from the threat of theft. Expensive cars were

stolen, disassembled and repainted.

Early

automobile thefts were performed by owners who would, “steal their own car.” To

collect on insurance, owners would strip the car of accessories and move it to

an out of the way location. The owner would work with a

thief: . . . the owner is in partnership with the thief. An

auto, for instance, that is insured for $2,000 is reported by the owner as having

been stolen. The machine is worth $1,500. So the owner, collecting his theft

insurance, makes a clean profit of $500.123

Owners in

debt often defrauded insurance companies as well: “an automobile owner, after

using his insured car for nine or ten months, discovers that its market value

is 40 percent lower than when first purchased; also the cost of maintaining the

machine, oil, gasoline, tires, repairs, etc., is considerably in excess of the

figure on which his first maintenance costs were based.”124

Quite

different in terms of criminal intent were the activities of the so-called

joy-rider. Joy-riders stole for thrills. In 1917, Secretary to the Detroit

Chief of Police, George A. Walters estimated that 90 percent of Detroit’s auto

thefts were performed by joy-riders.125 Joy-riders were often groups

of young men in pursuit of fun, and had a “taste for motoring.”126

One author argued that joy-riders (in all cases male) had a sexual motivation,

“Some young fellow with sporty tendencies and a slim pocketbook wants to make a

hit with some charming member of the opposite sex . . . he

thinks an automobile would help him in the pursuit of her affections.”127

After a joy-ride, automobiles were often found damaged and out of gas.

Historian David Wolcott has noted that in Los Angeles, “Boys approached auto

theft with a surprisingly casual attitude – they often just took vehicles that

they found unattended, drove them around for an evening and abandoned them when

they were done – but the LAPD treated auto theft very seriously.”128

In the early period of automobility, authorities considered “joy-riding” a

serious societal problem. Joy-riding was an action of a delinquent. Joy-riding

was so serious that young boys were prosecuted under the Dyer Act of 1919. The

federal government did not draw a distinction between joy-riding and

professional auto theft until 1930.129 Congressmen Dyer called for

the repeal of his own law, and to convince the U.S. House of Representatives of

the need for repeal, he read a letter from the superintendent of a

penitentiary:

Of the 450 Federal Boys in the National

Training School here in Washington, nearly 200 are violators of the Dyer Act,

with the ages distributed as follows: Two boys 12 years of age, 6 boys 13 years

of age, 19 boys 14 years of age, 31 boys of 15 years of age, 64 boys 16 years

of age, 48 boys 17 years of age, 19 boys of 18 years of age, 1 boy 19 years of

age, and 1 boy 22 years of age.130

Due to the capricious nature of theft for a joy-ride,

policemen and journalists surmised that it could be easily prevented: “It is

against this class of thief that the various types of automobile-locking

devices and hidden puzzles are effective . . . since the

joy-rider does more than half the stealing it follows that car-locks are more

than 50 percent effective in protecting a car.”131 However, more

elaborate means would be necessary to stop the professional thief.

Writers who

addressed auto theft from 1915 to 1938 admitted that the professional thief

could not be stopped. Professional thieves employed an array of tactics to

steal automobiles. Often chauffeurs, mechanics, and garage men became thieves.

Even though locks supposedly prevented theft by joy-riders, thieves would

simply cut padlocks and chains with bolt-cutters.132 Often this was

not necessary, since keys to early Fords were easy to obtain. In 1917, Edward

C. Crossman described the naïve Ford owner:

Ford owners take out the switch key on

the coil box and go strutting off as if they’d [sic] locked the car in the safe

deposit box. The first half-baked auto mechanic who needs a Ford can slip in

another key and depart via the jitney route without paying his fair.133

Crossman’s solution was to lock a heavy metal band around

the front wheel of the automobile.134 In a May 1929 article “Tricks

of the Auto Thief,” Popular Mechanics described

the array of tactics open to the automobile thief. Thieves stole accessories,

unlocked and started cars with duplicate keys, “jumped” the ignition by placing

a wire across the ignition coil to the spark plugs, ripped-off car dealerships,

and towed cars away.135 “Some thieves make a specialty of buying

wrecked or burned cars as junk . . . they receive a bill of

sale, salvage parts which they place on stolen cars, and so disguise the

finished automobile as a legitimate car for which they have the bill of sale.”136

One method called “kissing them away” involved an individual breaking into a

car, and being unable to start the ignition, a “confederate,” would push the

stolen car with his car from behind. The car would be moved into a garage or

alley and promptly dismantled.137 Thieves used interchangeable parts

to confuse authorities. In 1925, Joe Newell, head of the automobile theft

bureau in Des Moines, Iowa, stated, “the greatest transformation that takes

place in the stolen machine is in the clever doctoring of motor serial

numbers . . . this is the first thing a thief does to a

car.”138 Automobiles were branded with a serial number that

corresponded to a factory record, but thieves used several tactics to change

the numbers. The “doctoring” of numbers involved filing down numbers and

branding a new numbers into the car, or changing single numbers. In a detailed

article entitled “Stolen Automobile Investigation,” William J. Davis noted, “It

is possible for a thief to restamp a 4 over a 1; an 8 over a 3 where the 3 is a

round top 3; a 5 over a 3; to change a 6 to an 8, or a 9 to an 8, or an 0 to an

8.”139

Apparently

the joy-riding problem declined in the 1930s, but organized gangs emerged as a

more serious threat to steal automobiles and, in the process, vex authorities.

In Popular Science Monthy, Edward

Teale noted:

. . . the automobile

stealing racket in the United States has mounted to a $50,000,000-a-year

business. During the first six months of 1932, 36,000 machines disappeared in

seventy-two American cities alone. In New York City, $2,000,000 worth of cars

was reported stolen in 1931.140

Gangs developed sophisticated automobile theft operations

from the expert driver to expert mechanic. Gangs even developed their own

vernacular.141 A stolen car was a “kinky,” or a “hot short.” The

“clouter” actually stole the car and the “wheeler” drove it to the “dog house.”

The thieves were concerned with stealing the popular, mid-priced, widely-used

makes. Gangs often specialized in a certain make or model. One New York gang

“scrambled” the stolen automobiles: “a number of machines of the same make and

model are stolen at the same time . . . wheels are

switched, transmissions shifted, bodies’ changed, and engines transferred from

one car to another.”142

At other

times, gangs would use the “mother system.” Under this system, thieves stole a

certain make, had a fake bill of sale made, and changed all of the serial

numbers to be identical to the bill of sale. Ultimately, four or five of the

same car, with the same serial numbers and bills of sale would exist.143

In 1936, J. Edgar Hoover penned an article about gangster and international car

thief named Gabriel Vigorito (a.k.a. Bla-Bla Blackman), who had amassed a $1

million fortune from automobile theft.144 “The “hot car” depots of a

dozen states dealt in his goods . . . In Persia, Russia,

Germany, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and even China, the American car business

included many automobiles stolen from the streets of Brooklyn.” Authorities

convicted Bla-Bla to ten years in prison. Historically, the point is poignant:

the automobile trumped not only state lines, but national lines. The rise of an

industrial and global industry also rose with a global theft ring. In 1936, the

Roosevelt Administration entered a treaty with Mexico for “the recovery and

return of stolen or embezzled motor vehicles, trailers, airplanes or the

component parts of any of them.”145 The treaty prompted a convention

with Mexico in 1937 to address the stolen automobile problem.146

To control

rampant automobile crimes, authorities developed scientific means to fight

crime. As early as 1919, a system of fingerprints to identify automobile owners

was proposed.147 Throughout the 1920s, law enforcement of automobile

theft remained ineffective. By 1934, police developed sophisticated means to

monitor a more mobile public. In 1936 it was urged that “every city join the

nation-wide network of inter-city radio-telegraph service provided for by the

Federal Communications Commission.”148 Police developed processes

using chemicals and torches to identify fake serial numbers. Los Angeles police

department officers departed the station for their shift with a list of stolen

automobiles printed the night before.149 Developments in

communication aided police officers. “Chattering teletype machines and

short-wave radio messages outdistance the fleetest car, while police encircle a

fleeing criminal in an effort to make escape impossible.”150 Radio

communication made auto theft difficult. By 1934, “auto thieves found their

racket a losing one.”151 In response to mobile crime, Governments at

all levels grew more sophisticated. Insurance companies also grew more

sophisticated: “In Chicago, a central salvage bureau, maintained by insurance

companies is being established in an effort to wipe out a 10,000,000-a-year

racket in stolen parts.”152 Automobile manufacturers invested in a

“pick-proof” lock.153 From 1933 to 1936, insurance companies and the

government destroyed the market for stolen automobiles and stolen parts. In

1934 Popular Science Monthly reported,

“figures compiled by the National Automobile Underwriters Association show that

eighty-six percent of the cars stolen in 1930 were recovered while in 1931

eighty-two percent were recovered and eighty-nine percent in 1932.”154

What the above paragraphs suggest is that the

automobile placed unprecedented challenges before local, state, and federal

government agencies, and in response the responsibilities and scale of

government changed as a consequence. Indeed, the law itself changed, and that

included the area of tort law during the 1920s, as sorting out negligence as a

consequence of automobile accidents also posed new problems that demanded

innovative structural solutions.