|

| 1922 Essex Coach |

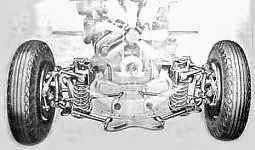

1934 Cadillac V-12 Knee Action

Cars as Homes

Since the

1920s, the home and the automobile have been inexorably linked.39

Perhaps a word should be said at the outset about psychological meaning of

these two things. The word home – and clearly very different than house – has a

meaning that is distinctive in American culture and in the English language.

For example, home is not exactly translatable in the Italian, French, or

Hungarian languages. It is a sacred place to many, a sphere in which

inhabitants shape a material environment that is essentially reflective of

self. For many individuals, the home is a place of relaxation, comfort, and

intimacy with others. The walls and ceiling of a home provide safety from the

elements and hostile others. The home is also a place of special objects. In

some cultures, the Middle East for example, the car dashboard contains numerous

trinkets. A generation ago, St. Christopher medals were attached to many

American dashboards. Not only did my parents always have a St. Christopher

medal in the car, they also had other non-essential gadgets from time to time.

For example, my cousin had a 1950 Oldsmobile with a vacuum-assisted pop-up bird

on the dash that responded to increases and decreases in acceleration. It was

like having a bird in a cage in the living room.

In any

case, typically for men, that special object attached to the home is often the

automobile, a possession that conveys status; for women, the things that mean

the most in a home are usually connected with loved ones or special people.

According to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eurgen Rochenberg-Halton, the home

“brings to mind one’s childhood, the roots of one’s being.”40 I can

certainly attest to this with regards to the car as an extension of the home,

as some of my first memories center on the dashboard, radio, ashtrays, lighter

and upholstery of my father’s 1948 Chevrolet.

For the car

to be an extension of the home, it had to be closed rather than open, unlike

the pre-WWI roadster or touring car. Thus, the first and undoubtedly most

important step in creating personal space in the automobile was the closed

steel body. Historian James J. Flink has called this development “the single

most significant automotive innovation.”41 Almost immediately after

World War I, public demand increased dramatically for a closed car that would

no longer be a seasonal pleasure vehicle, but rather all-weather

transportation. The few closed body cars built before WWI were extremely

expensive and the work of custom coach builders. This rise in demand during the

1920s, coupled with a remarkable number of concurrent technical innovations in

plate glass and steel manufacture, resulted in a revolution in production

methods, productivity and economies of scale. William J. Abernathy has

carefully characterized the transformation that took place on the shop floor

and assembly line, the first fruits of which occurred when in 1921 Hudson first

mass-produced a closed car. The transition away from rag tops (the word

convertible was first used in 1927 and officially added to the Society of

Automotive Engineers lexicon in 1928) was rapid and contributed to a venerable

prodigy of production by the end of the 1920s, as depicted in Table 4.

Table 4. Transition from Open to Closed Cars

|

Year

|

Open

Cars (%)

|

Closed

Cars (%)

|

|

1919

|

90

|

10

|

|

1920

|

84

|

16

|

|

1921

|

78

|

22

|

|

1922

|

70

|

30

|

|

1923

|

66

|

34

|

|

1924

|

57

|

43

|

|

1925

|

44

|

56

|

|

1926

|

36

|

74

|

|

1927

|

15

|

85

|

Source: John Gunnell, Convertibles: The Complete

Story (Blue Ridge Summit, PA: 1984), 129.

Significant

improvements in the quality of sheet steel were certainly part of this story,

but so too were developments in welding technology, the development of sound

deadening materials, and construction of the single unit body. All of these

innovations and far more were pioneered by the Budd Manufacturing Company.

Typical of the Budd All-Steel ads of the mid-1920s was one that appeared in the

Saturday Evening Post in 1926, with

the headline “Put the Protection of All-Steel Between You and the Risks of the

Road.”42 Like the safety inherent in a home, the steel body

protected its occupants, especially women and children. The ad continued, “Self

preservation is the first law on Nature. Today, with 19,000,000 cars crowding

the highways . . . With the need for safer motoring more

urgent than ever before . . . America is turning to the

All-Steel Body. It is the greatest protection ever devised to prevent injury in

the case of accident. See that your next car is so equipped!” A second 1926 Budd ad, like the first

mentioned, depicted a closed car traveling down a busy city street but in its

own clear lane, separated on both sides by huge sheets of steel that prevented

the masses of cars on each side from touching the car and harming its

occupants. The headline for this ad read in part, “The protection which it [the

all-steel body] brings to you and to your families is priceless – yet the cars

which have it cost no more than those which do not.”43

Clearly, the

message was that Budd-engineered closed body cars were worth the money spent.

The

rationale Budd used in ads published during the 1920s continued during the

1930s in the General Motors ads featuring the “Turret-Top” design that

contained such sentences as, “The instant feeling of security you

get . . . is beyond price.”44 Surprisingly

perhaps, the pitch toward safety was far more prevalent in ads of the 1930s

than one might think, although ironically during the early 1930s convertibles

were the center of many ads, even when closed cars were pictorially featured!45

On the eve of WWII, however, the theme of the home and the car was clearly

brought together, as reflected in a Hudson advertisement featuring a beautifully

attired woman sitting in a plushy upholstered rear seat. The ad touts the

availability of “a wide selection of interior color combinations that harmonize

with the exterior colors . . . at no extra cost!” This ad

has clear-cut similarities in terms of an emphasis on color and comfort to

paint ads of the same period, as exemplified by the Sherwin-Williams Paint and

Color Style Guide of 1941.46

In

automobiles, up to now, one upholstery color has usually done duty with every

body color. Carpets, floor mats, steering wheels, and trim have introduced

still other assorted colors and tones.

Now

Hudson’s Symphonic Styling gives you, in your 1941 car, the kind of color that

permit a wide variation in the details and equipment of each individual car,

without interfering with orderly, efficient mass production. Symphonic Styling

is the climax of this long-time development.47

With the

widespread adoption of the closed body car by the late 1920s, automotive

engineers next turned their attention to the suspension system.48 To

the uninitiated, suspension system engineering involves very complex mechanics

and geometry.49 One area of concern focused on shock absorbers or

dampeners. In addition to mechanical and hydraulic improvements, air springs,

or the insertion of an inflatable inner tube inside a coil spring, was one

strategy developed during the 1920s and 1930s to improve ride. A second

involved driver control of the shock absorber system, and in 1932 Packard

pioneered a Delco-Remy unit in which a cable mounted on the dash vastly

enhanced ride quality and handling.50 The most important innovation,

however, was the introduction of independent front suspension.51

First used by Mercedes in 1932, independent front suspension was installed in

Cadillac, Buick, Oldsmobile and Chrysler vehicles in 1934, with Ford only

adopting this technology after WWII. Pre-war Pontiacs and Chevrolets employed a

not nearly as effective Dubonnot design. The potential advantages of

independent front suspension, however, were never fully realized, however.

The closed

body style was designed for all-weather driving, as previously mentioned, but

it took several decades before climate control within the personal space of the

automobile became efficient and widely introduced. Beginning around 1925,

aftermarket manufacturers began to sell hot water type heaters for American

automobiles.52 The problem of heating the car was more difficult

than what one might initially think: proper controls and the mixing of heated

air coming from a heat exchanger with ventilated fresh air did not take place

until 1937, when Nash introduced its WeatherEye system. Variants of the Nash

system were introduced by Buick in 1941 and Ford in 1947 (Magic Air).

Air

conditioning, and the development of an integrated heating/cooling system

lagged by perhaps only a decade or so behind hot water heater technology.53

From its inception, air-conditioning was touted as a feature that would exclude

noise from the outside. During the late 1930s Packard pioneered an early

system. An early Packard ad proclaimed “you can step OUT of summer heat – when

you step INTO your stunning new Packard.’ The air-conditioned Packard created a

private, personal place.

And – don’t shout, they can hear

you! In the superbly comfortable

air-cooled Packard, you ride free from open-window traffic noise and the rush

of the wind which so often carries away one’s words with it! In this greater silence front and rear

passengers converse with ease and complete audibility. You enjoy a ride that is

infinitely more restful than you have ever experienced.54

One final

technology that offered to transform the car into a home-like environment was

the radio. Surprisingly, perhaps, there is not one scholarly essay that

explores how two dynamic technologies were brought together beginning in the

1920s.55 Early on, the main technological bottleneck centered on

multiple battery power supplies that were compatible with existing tube grid

and filament voltage requirements. In 1929, based on the work of William Lear,

the Galvin Manufacturing Corporation introduced the first successful car radio,

the Motorola Model 5T71. A year later, other manufacturers entered the fray;

for example, the Crosley Corporation introduced its first car radio, the

“Roamio.” In 1932 Mallory and other manufacturers produced several new power

supplies, and four years later Ford was the first to install a radio

tailor-made for the dashboard. It was claimed that among other advantages, the

radio in a car would ensure that one could listen to favorite shows without

missing them. “When it’s a quarter before Amos ‘n’ Andy or Lowell Thomas and

you’re in the ol’ bus, far, far, from home and radio, is it a tragedy? Or you

can tune in right where you are?”56 Thus the home was again extended

to the car. This was also one theme among several that was employed in

advertising. For example, a 1934 Philco auto radio ad asserted, “Enjoy Philco

in your car . . . as you do at Home! You wouldn’t be

without a radio at home – why be without one in your car? Just as a PHILCO

brings you the finest radio entertainment in the comfort of your living room, a

PHILCO Auto Radio gives you the most enjoyable radio reception in your car.”57

Contrary to other technologies discussed above that stressed the safety angle,

in 1939 psychologist Edward Suchman argued that listening to the radio

distracted the driver from the road.58 Suchman’s applied

psychological study was a response to a long-standing criticism of the radio in

cars, for when introduced in 1930 several states refused to register vehicles

with radios, although apparently this was never enforced.

No comments:

Post a Comment