Industrial America: The “Carnival of Speed” and the Indianapolis 500

It was industrial America that shaped auto racing and capitalist America cast the sport into a “Carnival of Speed.” To alleviate the risk to spectators and to ensure a paying audience, automobile racing transitioned from open road courses to closed tracks. This new phase was inaugurated in 1909, when the American Automobile Association took on organizational responsibility for the sport. At the same time, entrepreneur Carl Graham Fischer and partner James A. Allison had a 2.5 mile oval constructed 4 miles from downtown Indianapolis using crushed stone as a surface. Racing began at Indy in 1909, but the problem of thrown rocks and injured drivers and mechanics resulted in later paving the track with bricks.

1909

The “Carnival of Speed” and the Indianapolis 500

3 dead in 1909 RaceIn 1911 the first 500 mile race took place on Decoration (later Memorial) day, with driver Ray Harroun winning the inaugural race without a riding mechanic and using a rear view mirror.

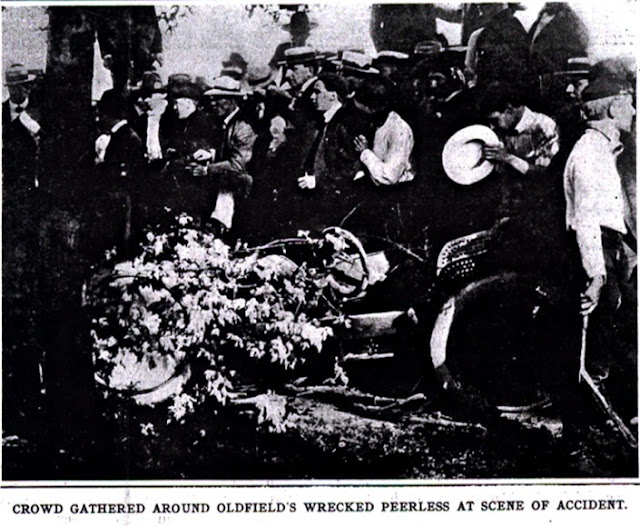

At the time critics were calling for an end to racing due to the high death toll. Even driver Barney Oldfield got into the debate, stating that “I was never famous until I went through the fence at St. Louis and killed two spectators. Promoters fell over one another to sign me up.”

1904 St. Louis In addition to the major races sanctioned by the AAA, there were hundreds of other events held at state fairs and by “circus” barnstormers. Randall L. Hall characterized the early sport as one linked to manufacturers with the vague promise that the mayhem was somehow connected to technical progress, while in fact in reality it was a commercial spectacle.

Industrial America spawned automobile racing. In this sport, individuals compete for prizes by operating complex machines at the fastest speed possible. They travel a designated course and follow strict rules. Fans far removed from participation pay for the privilege of watching (and hearing, smelling and feeling) the spectacle. “Carnival of speed” was the label given to many early races. This characterization is apt, for automobile races are simply particularly modern form of show business, a circus on wheels. And like other niches of entertainment industry, racing’s success lies in organizing and promoting the product.

By 1913 with the entrance of three French Peugeots in the Indianapolis 500 field, the race became a battle of nations.

French race car driver Jules Goux (1885-1965) winning the Indianapolis 500 on May 30, 1913

J.C. Burton’s poem, published in Motor Age, reflected the nationalistic sentiments of the day:

"O! my sons, give heed to the gods of speed

When they call on you today;

There's a race to run form the starting gun

Till the bolts and nuts give way;

And the call to fight is a challenge old

From the men who dare to the men who're bold.

Thus does the Motherland implore her sons

With nerves of steel

To Conquer Space in grueling race and grind

Time 'neath the wheel;

Full well she knows to what rare heights

Her daring sons aspire,--

Projectile laws are shot with flaws before

Supreme desire…."

The French reigned supreme at Indianapolis between 1913 and 1916. But with World War one and the coming of the Duesenberg brothers and Harry Miller, the winds of racing supremacy between Europe and America soon shifted. In 1916 Miller rebuilt a Peugeot engine for driver Bob Burman, and in the process began designing and building power plants superior to the pre-war Peugeot twin cam, 4 valve per cylinder engines. Such was the transition that in 1921, driver Jimmy Murphy, piloting a Miller-powered Duesenberg, won the French Grand Prix race, the first American to do so.

Jimmy Murphy 1920 Thus, at the opening of the Roaring Twenties, Americans not only could make very fast cars more than competitive on the world stage, they could also make inexpensive cars for the masses, thanks to Henry Ford.

No comments:

Post a Comment